Icelandic music thrives against all odds

Reykjavík is a paradox. The tiny Icelandic capital has produced a music scene that is far greater than its size warrants.

Los Angeles, New York and London. Artists and the creative industries tend to flock around the world’s great cities.

But even with a modest population of 120,000, Reykjavik has managed to produce a music scene where international successes such as Björk, Sugarcubes, Mugison, Múm, Sigur Rós and Gus Gus are fighting it out as favourites among the world’s reviewers and music fans.

Financial crisis didn’t kill off the initiative

Iceland’s annual Airwaves music festival is considered to be one of the world’s leading music festivals, and whereas music sales are on a rapid decline elsewhere, Icelanders continue to buy music despite the country’s dramatic financial crisis.

It is this paradox that prompted sociologist Nick Prior of the School of Social and Political Science at Edinburgh University, Scotland, to take a closer look at Reykjavik.

Reykjavik is small, but it’s not a village. It’s a modern city that’s hugely competitive. There’s only one main street, and it acts as a creative hub. This is where most of the musicians I have interviewed live, and this is where all the music venues are located.

At a recent conference on pop music in the Nordic region, held at Roskilde University in Denmark, he presented the early findings of the fieldwork and the interviews he has carried out with a number of players on the Icelandic music scene.

Don’t want to sound like the band next door

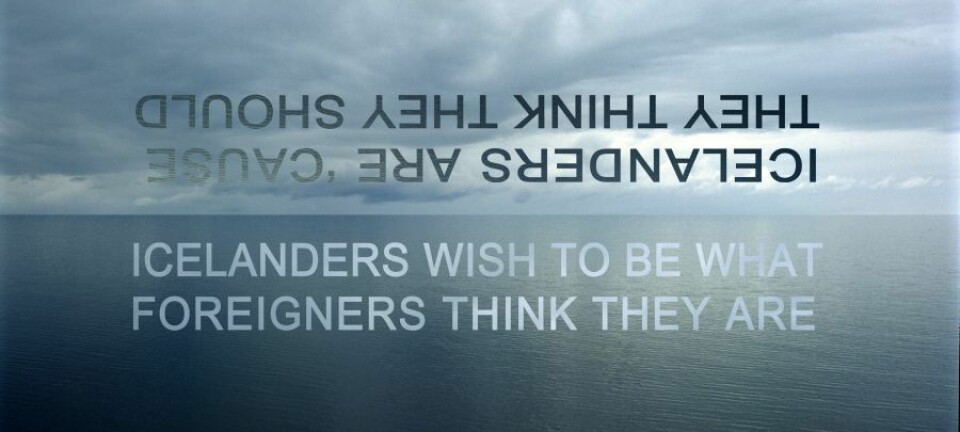

Small towns are not usually the ideal place to stand out from the crowd. Diversity and creativity are normally thought to thrive in the world’s top cities. But according to Prior, Reykjavik adds a few new nuances to this conception.

“Reykjavik is small, but it’s not a village,” he says. “It’s a modern city that’s hugely competitive. There’s only one main street, and it acts as a creative hub. This is where most of the musicians I have interviewed live, and this is where all the music venues are located. This means that there’s a very close contact between the actors in the local music scene.”

They also share the few rehearsal rooms that the city has to offer. But according to the researcher, this does not result in a standardised sound; rather, it makes them even keener to develop their own distinctive sound and be original.

Pretty much every Icelandic town has its own choir, and these choirs play a major part in social life. It’s as natural for Icelanders to sing as it is to go into a swimming pool, and that’s a frequently overlooked fact when we’re talking about creative industries.

“It’s very important not to sound like the band in the rehearsal room next door. This creates a strong desire to be original and innovative,” says Prior.

Too small to be snobbish

In the big cities, musicians tend to arrange themselves into subcultures with others who make the same type of music. But this isn’t really possible in a small city like Reykjavik:

“Of course, there are subcultures in Iceland too, but they don’t exclude musicians from other subcultures in the same way that we’re seeing in other Nordic countries. Often there are only a small number of people who are deeply involved in a given subculture, so it’s not wise to lay all your eggs in that one basket. This means that the musicians need to be more open to other styles,” he explains.

“Most Icelandic musicians play in more than one band, and I believe that’s one of the things that make the musicians more open to other styles. And at the same time they’re learning something by playing different types of music.

Many of the younger musicians have used their anger towards the banks and the politicians as a catalyst for making new music. Some of the bigger bands that had turned into small businesses have obviously felt the rising taxes, but they, too, have managed to vent their anger towards the political system through their music.

“The friendships tend to cross the genre boundaries because they simply have to work with musicians from genres other than their own – so they can borrow instruments, share rehearsal rooms.”

All this intimacy is, however, not only positive, says the researcher, since it can also make the musicians reluctant to criticise one another because of this close interdependence.

The voice is Iceland’s prime musical instrument

The history of Icelandic music is also a history of scarcity. According to the researcher, it took quite a while before traditional Western European musical instruments found their way to Iceland.

“There may have been instruments that haven’t survived to the present day, but until the mid-19th century, only a couple of traditional string instruments were being used. The classic Western European instruments are more or less absent. For a long time, there were no pianos, no violins and no cellos. The Icelanders tried to import organs and other instruments, but they couldn’t survive the Icelandic climate.”

Prior believes this has meant that there has been a special focus on the voice as a musical instrument in Iceland.

“This is e.g. reflected in the many choirs in Iceland. Pretty much every Icelandic town has its own choir, and these choirs play a major part in social life. It’s as natural for Icelanders to sing as it is to go into a swimming pool, and that’s a frequently overlooked fact when we’re talking about creative industries.”

Making the most of scarce resources

The Icelanders’ ability to get the most out of scarce resources also meant that they were quick to embrace the do-it-yourself attitude of the punk movement when this genre swept across the country – slightly delayed – from the British Isles.

”Punk had an enormous influence. The do-it-yourself attitude found a natural place in the Icelandic mentality, and it has been crucial in relation to the many independent record companies that have been set up in Iceland. Even to this day, none of the major international record companies are represented in Iceland,” says the researcher.

Punk attitude helpful in crisis

This mentality may well have helped the Icelandic music scene through the country’s financial crisis.

“The economic collapse of 2008 has actually not had much of an impact on the Icelandic music scene, since there was never really much money there in the first place. In a way, the punk attitude has helped the musicians through the crisis,” says Prior.

“Many of the younger musicians have used their anger towards the banks and the politicians as a catalyst for making new music. Some of the bigger bands that had turned into small businesses have obviously felt the rising taxes, but they, too, have managed to vent their anger towards the political system through their music.”

----------------------------

Read the Danish version of this article at videnskab.dk

Translated by: Dann Vinther