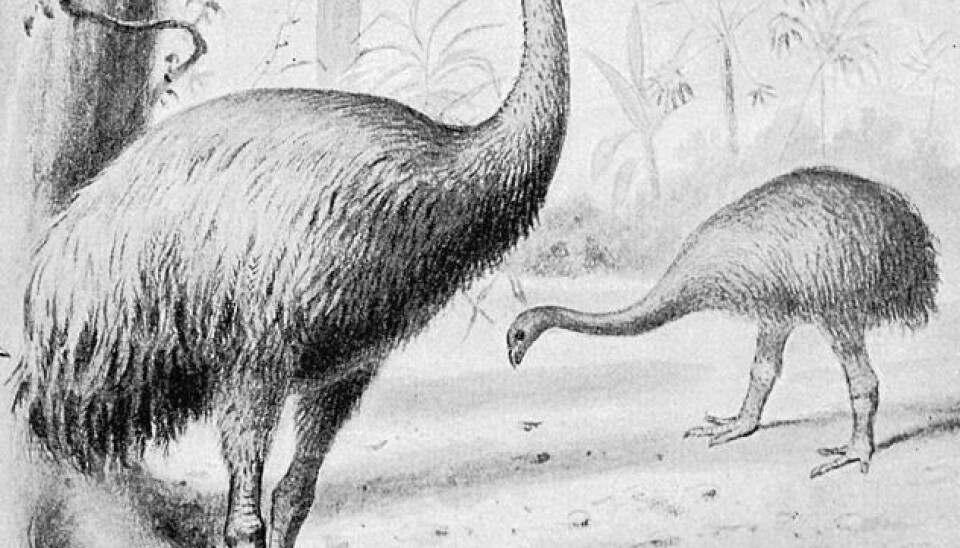

Humans alone killed off the giant moa bird

New research reveals that the moa population were fit and healthy before humans started hunting the bird. In spite of this, it took less than 200 years before the gigantic bird had died out.

Was New Zealand’s giant moa bird killed off only by humans or were factors such as climate change and volcanic eruptions also involved? This question has been hotly debated among scientists for many years, but now a Danish researcher closes the debate with compelling evidence.

In a new study, Morten Allentoft, a postdoc fellow at the Centre for Geogenetics at the Natural History Museum of Denmark, shows that the moa population were doing just fine before the first humans settled in New Zealand some 700 years ago.

The research, which is the result of a long-term collaboration between scientists from Denmark, Australia and New Zealand, reveals that the giant bird was eradicated by contact with humans only, and that neither volcanic eruptions, climate changes or diseases occuring before human arrival had anything to do with it, as other researchers had suggested.

It is therefore also interesting to note that the giant birds vanished less than 200 years after the Polynesian settlers had arrived.

Our notion of the noble savages who lived in harmony with nature is mistaken. The beautiful co-existence is an illusion. We have long known that humans contributed to the extinction of the moa, and we can now prove that humans were the only cause. The population did just fine before we humans reached New Zealand.

Morten Allentoft

”Our notion of the noble savages who lived in harmony with nature is mistaken. The beautiful co-existence is an illusion. We have long known that humans contributed to the extinction of the moa, and we can now prove that human contact was the only cause. The population did just fine before we humans reached New Zealand,” says Allentoft.

New study debunks old study

It was previously assumed that the moa were already close to extinction when the Polynesians sailed over the sea to New Zealand.

Several scientists have come up with suggestions on how the moa had already run their allotted span on Earth before we humans gave them the final nudge.

In 2004, a genetic study also suggested that the moa were in rapid decline in the millennia before the Polynesians arrived.

However, according to Allentoft, these previous interpretations were based on very small datasets and some simple models, and genetic analysis methods have seen great improvements since then.

The improved methods used in the Danish study reveal an entirely different picture:

“By analysing DNA from almost 300 individuals from four moa species, we now have a much more solid result. It shows that none of the four moa species that we examined underwent a decline in genetic diversity for 5,000 years before humans arrived in New Zealand. The population was fit and healthy, and had been fully capable of living well if we humans had not killed it off,” says the researcher.

The moa had high genetic diversity

In the study, Allentoft and colleagues looked at fossil DNA from 281 moa bones, spanning a period from 13,000 years ago until humans landed on New Zealand’s shores around the year 1300.

They dated the bones using the carbon-14 dating method, after which they sequenced the DNA from the bones in order to form a picture of how high the genetic diversity was in the moa population in the period leading up to its extinction.

Unlike the 2004 study, where the researchers only studied mitochondrial DNA, the new study also analysed nuclear DNA in the form of so-called microsatellites, which gives a much higher level of resolution in the analysis, leading to a more solid result.

The new analysis showed that the moa gene pool was fit and healthy and showed no signs of inbreeding or low genetic variation, as in a small and declining population.

”There is a correlation between genetic diversity and population size. When a population collapses, this is clearly reflected in the genetic diversity of the population. We do not see this in the moa, which maintained a very stable gene pool,” says Allentoft.

”We also carried out a number of data simulations of various population scenarios, which all show that the population was not about to collapse. Our data actually shows the exact opposite: that the moa population was probably on the increase right up to the point when humans arrived.”

Extinction not only due to hunting

The new findings may settle and old scientific dispute, but they do not specify exactly how the moa became extinct. Although it does establish that humans were the cause, the study does not say anything about how we caused the extinction.

Allentoft has no doubt that hunting is one of the causes, but other factors may have played a role, too:

”We know that the first Polynesians brought rats with them to New Zealand. Maybe the rats got a taste for the bird’s eggs or its young. It is also possible that humans brought some diseases with them, which then spread to the moa. We do not know,” he says.

”What we do know, however, is that there are plenty of moa bones in the earliest kitchen middens in New Zealand, and that it took less than 200 years for the settlers to kill off the moa. So from this perspective, our notion of a beautiful coexistence between our wild ancestors and Nature is an illusion.”

------------------

Read the Danish version of the article at videnskab.dk