How Hitler decided to launch the largest bike theft in Denmark’s history

Hitler personally approved the decision to confiscate bikes in occupied Denmark during the war, revealing the internal power struggles among the Nazi occupiers.

12 October 1944, Adolf Hitler is in his military headquarters Wolfsschanze (Wolf's Lair) on the Eastern Front from where he commands the battle against Stalin’s troops.

But in the middle of the Soviet advance, and with the US and UK armies encroaching from the west, he still found time to deal with more trivial political issues.

On this particular October day Hitler personally approved the commencement of the largest bicycle theft that the bike-crazy nation of Denmark had ever witnessed. The event has been described in a new study recently published in the journal Historisk Tidsskrift.

“He probably didn’t spend more than two minutes on it, but we can see in the archive material that the issue was discussed. Hitler approves the suggestion from his foreign ministry, which is that all newly produced, Danish bikes and bikes on sale should be confiscated,” says lead-author John T. Lauridsen, Head of Research at the Danish Royal Library.

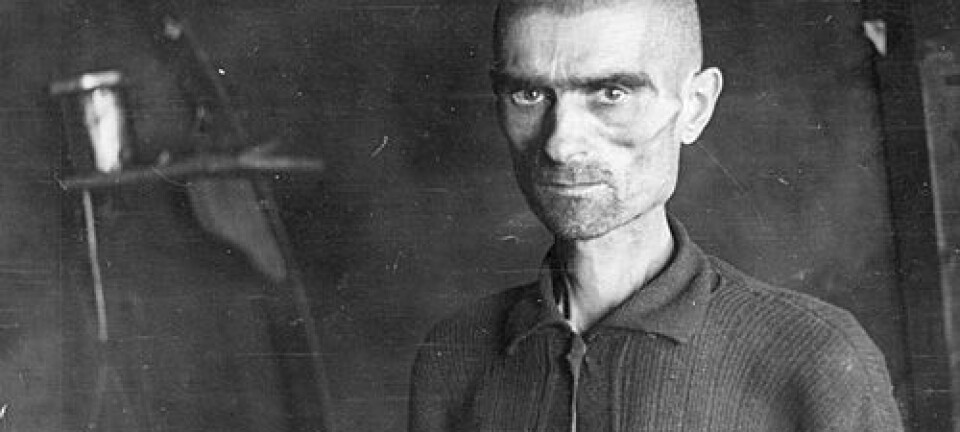

Lauridsen has dug through German and Russian archives, as well as thousands of documents from the German Nazi authorities in Denmark that documented the comings and goings of the German civilian administrator in Denmark, Werner Best, during the war.

It was because of Best, that Hitler starting thinking about Danish bikes. And his decision is one of the few cases in which he, himself, was directly involved in the rulings of the occupied Nordic country.

Read More: Nazis used own laws on German-Norwegian homosexuals

Hitler’s bike theft concealed internal power struggles

Bike theft may seem a minor incident in Hitler's back catalogue of crimes, but the archival material of the incident reveals the intense and often bitter power struggles among the German occupation forces.

There were fierce internal rivalries and conflicting interests among the Germans, says Lauridsen.

“Back then these struggles were hidden,” says Lauridsen. “But there was a massive discord between the Gestapo, The Wehrmacht (the German army), and the civilian authorities.”

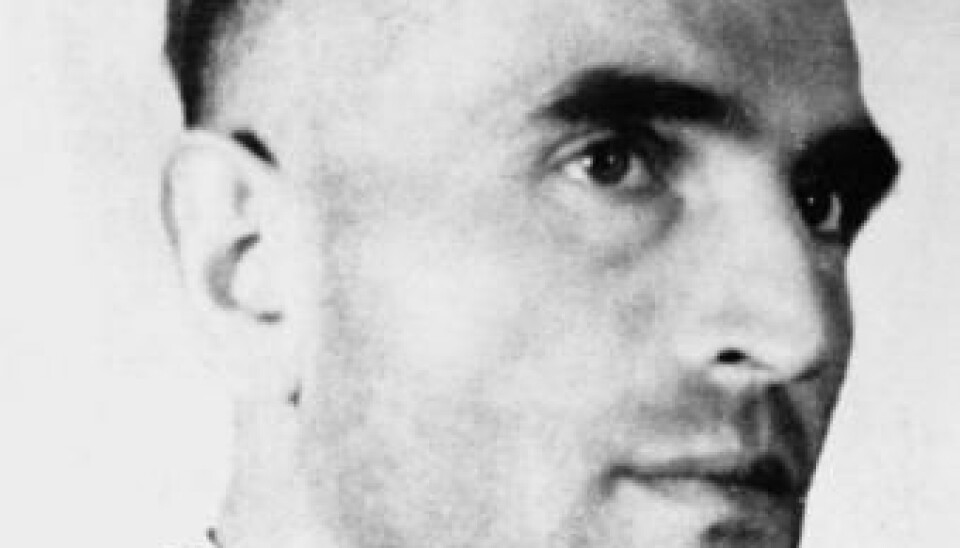

The German Army was under the command of General Hermann von Hanneken, but the Danish branch of the Gestapo was led by SS General Günther Pancke. Werner Best had been sent to Denmark by the German Foreign Ministry to lead the civilian authority.

“They all had very different interests to safeguard. The war increased these pressures, and a rift developed between Pancke, von Hanneken, and Best,” says Lauridsen.

A covert play for power

The bikes were seized following an order from the German armed forces on 6 October 1944, instructing authorities to seize all bikes in Italy, Holland, and Denmark.

The order was in response to fuel shortages and bikes were needed as a replacement form of transport.

General von Hanneken knew all too well that it was up to Best to decide which bikes were confiscated, and how many. And Best took the opportunity to strengthen his own position and weaken that of both Pancke and von Hanneken, says Lauridsen.

“Best went to his bosses in the German Foreign Ministry and said he had been instructed to confiscate all Danish bicycles, which he found worrisome. The ministry and the Minister, Joachim von Ribbentrop, was internally weak at the time, and he didn’t dare overturn the army’s orders on his own,” says Lauridsen.

Read More: Jutland: Why World War I's only sea battle was so crucial to Britain's victory

Bikes were an important means of transport

It may seem odd that the highest levels of government were so concerned with bicycles. But it just goes to show what a vital form of transport they were in occupied Denmark.

“It’s hard to understand today, but bicycles were central in enabling the labour force to travel around the city and the countryside,” says Lauridsen.

“People biked long distances to get to work, and it would have been a big blow to industry and agriculture if all bikes were confiscated,” he says.

For Best, his most important task was to ensure the secure transport of food from Denmark to Germany, and to do that he needed peace on the streets.

He recommended that only new bicycles and bikes that were already on sale in the stores were confiscated.

But as Von Ribbentrop's position was weakened at the time, he did not dare take the decision. Instead, the issue went straight to Hitler himself.

A German power struggle

But why would Best risk wasting Hitler’s time and keeping his own bosses at the German Foreign Ministry in the dark over something he could have decided on himself?

The answer is due to the internal power struggles among the Germans, says Lauridsen.

“The first years of occupation were peaceful, and there was no major popular resistance. But in 1944, [increasing] acts of sabotage meant that the Danish police was dissolved. The Gestapo had arrived in the country in the autumn of 1943 – before that, the Danish police were responsible for arresting local opposition,” he says.

Read More: Punished without trial for sleeping with the Germans

Everyone had their own vested interests

Pancke, von Hanneken, and Best all had their own interests and ways of pursuing them, says Lauridsen.

Von Hanneken was responsible for the defence of Denmark against an Allied invasion and maintaining supply lines to Norway, where resistance to German occupation was much higher than in Denmark. For that reason, Von Hanneken demanded harsh methods against saboteurs attempting to damage the Danish railway lines.

He demanded that civilians keep watch along the railway tracks, and he made lists of prominent people, such as actors, judges, editors, and politicians who could be taken hostage in case of a popular uprising or invasion.

Pancke used similarly harsh methods to quell potential uprisings. He was ordered to murder civilians in revenge for any sabotage and killing of German soldiers in Denmark, and executed saboteurs without trial.

“Best on the other hand tried to dampen conflicts,” says Lauridsen. “He played the food card as often as he could. He was politically responsible, collaborated with the Danish authorities, and didn’t want to escalate conflicts that could cause turmoil.”

Denmark was treated gently

Best’s plotting paid off. And Denmark was relatively peaceful compared with other occupied countries, such as Holland, Poland, France, and Norway.

“Random shootings of German soldiers were almost non-existent in Denmark, and retribution was not as tough as elsewhere. In Eastern Europe, the SS razed villages to the ground or executed people without any particular reason. Hitler demanded ten civilian deaths for each assassinated German soldier. In France, the figure was nearly 100 for each German. In Denmark it wasn’t even a one to one ratio,” says Laruidsen.

Danes also benefited from other freedoms that were denied to citizens of other occupied lands during the war.

“One myth about the Danish occupation was that listening to the BBC was forbidden. But it was actually permitted,” says Laruidsen.

Best had many victories over his German colleagues, but this did not mean that he was acting in the interest of Denmark.

“Make no mistake. He was a calculating and cynical Nazi. Everything he did, he did for the Third Reich. His motive was to secure Denmark’s willingness to supply goods,” says Lauridsen.

Read More: Norwegian industry complied with German war efforts

Denmark’s largest ever bike theft

Ultimately, Hitler approved the bike seizure. Much to the anger and frustration of the Danes.

Officially, it was called an acquisition, as the owners were able to apply for compensation from the state. But in reality it was theft. And Denmark never received a penny for the bikes.

Illegal newspapers, circulated among the Danish people, ridiculed the Germans and referred to the bicycles as “Hitler's secret weapon.”

A short-lived political victory for Best

Associate Professor Niels Wium Olesen from Aarhus University, Denmark, calls Lauridsen’s work impressive.

“The bike theft is a good example of how the German regime operated in Denmark,” says Olesen.

Best’s victory however, was short-lived, he says. And as the war progressed, his influence in the German ranks started to subside.

“There was a shift in German interests. As the Germans were losing the war, the military perspective became more important and politics less so. This meant that Hermann von Hanne’s role became more substantial and Best's position diminished,” says Olesen.

Lauridsen agrees. Best did not secure any substantial, long-term gains in personal power or influence, he says.

“Perhaps it gave him a small victory in the short-term. But the German army command had left it open for him to determine the extent [of the seizure]. The German Foreign Ministry realised that he’d cheated them, but watched over him because Denmark was the only occupied country where they had so much influence,” says Lauridsen.

-------------

Read the Danish version of this article on Videnskab.dk

Translated by: Catherine Jex