How the heavy plough changed the world

New technology ploughed its way to prosperity in medieval Northern Europe.

The world changed when a plough that could plough deep and turn over heavy clay soil was invented in the Middle Ages.

Armed with massive amounts of data, researchers are now trying to document how a small technology leap turned the distribution of wealth on its head in medieval Northern Europe.

The invention of the heavy plough made it possible to harness areas with clay soil, and clay soil was more fertile than the lighter soil types. This led to prosperity and literally created a breeding ground for economic growth and cities – especially in Northern Europe.

Good times with heavy soil in the North

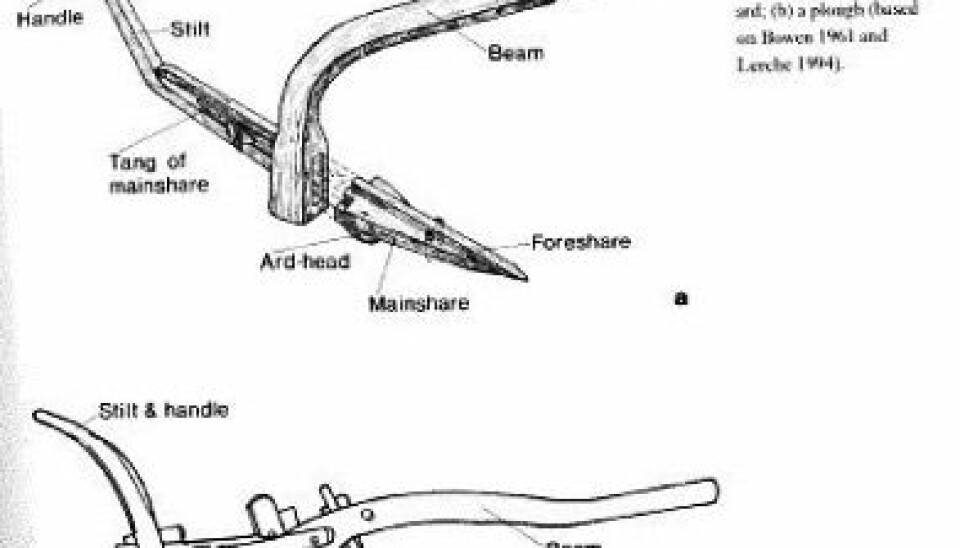

Loose, more sandy and dry soil is more common in Southern Europe, where farmers were doing fine with the earliest functioning plough – known as the ard, or the scratch plough.

The heavy plough turned European agriculture and economy on its head. Suddenly the fields with the heavy, fatty and moist clay soils became those that gave the greatest yields.

This type of plough wasn’t, however, very good for ploughing the heavier, more clayey soils up north. For this reason, it was mainly the south that experienced prosperity and growth with growing cities all the way up to the early Middle Ages.

“The heavy plough turned European agriculture and economy on its head. Suddenly the fields with the heavy, fatty and moist clay soils became those that gave the greatest yields,” explains Professor Thomas Barnebeck Andersen of the University of Southern Denmark.

“The economy in these places improved and this sparked the growth of big cities with more people and more trade. The heavy plough started an upward spiral in new areas.”

Together with Associate Professor Peter Sandholt Jensen and PhD student Christian Skovsgaard, Andersen is looking into how – and if – the heavy plough changed the world in the early Middle Ages from around year 900 to 1300.

New inventions turn cons into pros

The economy in these places improved and this sparked the growth of big cities with more people and more trade. The heavy plough started an upward spiral in new areas.

At that time an agricultural revolution was taking place, which led to far higher yields and more efficient operation than before. Some historians believe the main reason for this revolution – which took place while economic growth centres were moving from the south up to the north of Europe – was the invention of the heavy plough.

“The stirrup is another example of a small yet crucial invention from the Middle Ages. It enabled warriors to sit steadily on a horse and transfer the horse’s strength to e.g. a lance. This marked a change in warfare practices,” says Andersen.

“Those who were first to start using this technology usually emerged as the victors. The heavy plough represented the same advantage for regions where the soil was difficult to cultivate.”

Historian Lynn White Jr. presented the theory about the heavy plough in a book back in 1962. But as early as around World War 2, he had already introduced this and other unconventional hypotheses. These were about how seemingly small, new technologies had a sudden and dramatic effect on the economic development, and therefore also determined where the power was centred and where cities grew.

Uncovering the agricultural revolution

Historians normally find their sources and draw up hypotheses by digging deep into selected qualitative source material. In contrast to this, the Danish project involves the comparison of enormous amounts of data.

“The theory about the heavy plough has never been tested the way we’re doing now,” says the Andersen.

“By quantitatively combining a great deal of facts and databases, we’re now able to exclude with greater precision influences other than the heavy plough. At the same time we’re also taking soil conditions, growth centres, geology, climate and a host of other relevant factors into consideration to support or reject our hypothesis.”

Simply stated, the Danish researchers’ hypothesis is based on the so-called geography hypothesis, which states that a geographical condition (e.g. heavy clay soil) becomes an advantage when a new technology (e.g. the heavy plough) becomes available.

”We’re primarily focusing on a single crucial technological innovation that we can use as a starting point for explaining the extensive displacements of growth centres in Europe,” says the professor.

The heavy plough viewed from multiple angles

Once all the various factors have been analysed, they are then related to the introduction of the heavy plough in the various regions of Europe.

The three researchers set out to test the ‘heavy plough hypothesis’ back in 2011. The preliminary results appear to support their theories about the enormous importance of the heavy plough.

And again it’s all about new technology – this time in the form of databases and advanced computer software, which makes it possible to compare the results.

”We’re talking huge quantities of data that we extract from widely different databases,” says Andersen.

Econometrics: the economic research approach

The researchers will rely extensively on Geographical Information System (GIS) software to generate a number of the measures needed. The GIS software allows us to generate a unique dataset with a number of variables otherwise impossible to obtain.

”This type of research has only been possible in the past decade, with new and sophisticated software and an integration of lots of administrative and scientific data. For instance, we use the European Nomenclature of Territorial Units for Statistics (NUTS) in conjunction with GIS data from a geographical information system.”

Many factors must be considered to get to fully understand the importance that the heavy plough had as a new technology.

The first step basically consists of figuring out how the soil types are distributed in different regions – of which Europe has 270, according to the GIS matrices.

Clay soil is the first indicator – others follow

”Clay soil is known as luvisol. This is what we’re looking for and what tracking databases use,” says Andersen.

Once the luvisol-rich land has been detected, the next unknown parameters pop up:

- Where exactly are the luvisol-poor soils? Developments in the early Middle Ages can then be compared with luvisol-rich regions.

- Where were the financial centres located – before and after the introduction of the heavy plough?

- How and when did urban centres and populations start growing?

- How might other factors – including other new technologies, political and historical factors – have affected the rise or fall of these centres?

- What do written sources say?

-----------------------------------------

This article is produced in collaboration with the Danish Council for Independent Research (DFF).

Read the Danish version of this article at videnskab.dk

Translated by: Dann Vinther