How fake larvae revealed predator patterns around the world

Scientists released an army of fake insect larvae to investigate how predators attack their prey—the tropics officially win as the world’s “hardest place to survive.”

If you are an insect born in Borneo, you should seriously consider packing your bags and moving to Greenland. The risk of being eaten by predators is eight times lower here than in areas close to the Equator.

These are the conclusions of a new study, recently published in Science, which is the result of a collaboration between 40 scientists from 21 different countries.

The new study answers a long held question on whether the relationship between predators and prey change according to region. The new study confirms that this is the case, however, the scientists cannot explain exactly why this is.

40 scientists used same type of glue and pen

One of the 40 scientists in the study is senior scientist Martin Schmidt from the Department of Bioscience at Aarhus University, Denmark.

Schmidt studies Arctic population ecology at the Zackenberg research station in Greenland, and like his 39 colleagues, he went out into nature and painstakingly placed fake, green larvae on plants. All the scientists involved in the study used exactly the same type of materials and methods.

This is the big strength of the study, says Schmidt.

“We’re the first to discover a pattern using a completely standardized method. The experiment has been controlled centrally and it’s really nice because we can say with confidence that the pattern is not just due to the different methods,” he says.

Schmidt’s data represent one of the geographical extremes—the Poles—in the new study.

2,879 insect larvae became overweight

In total, 2,879 fake insects were deployed and monitored around the world within a period of 4 to 18 days.

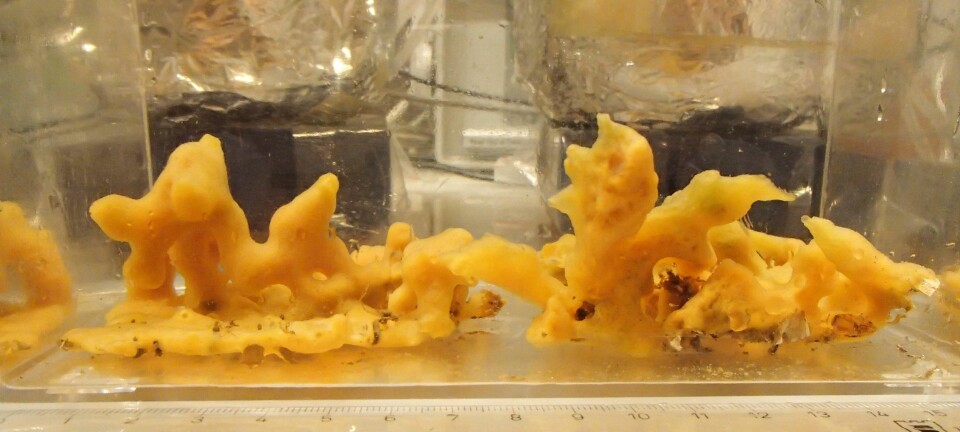

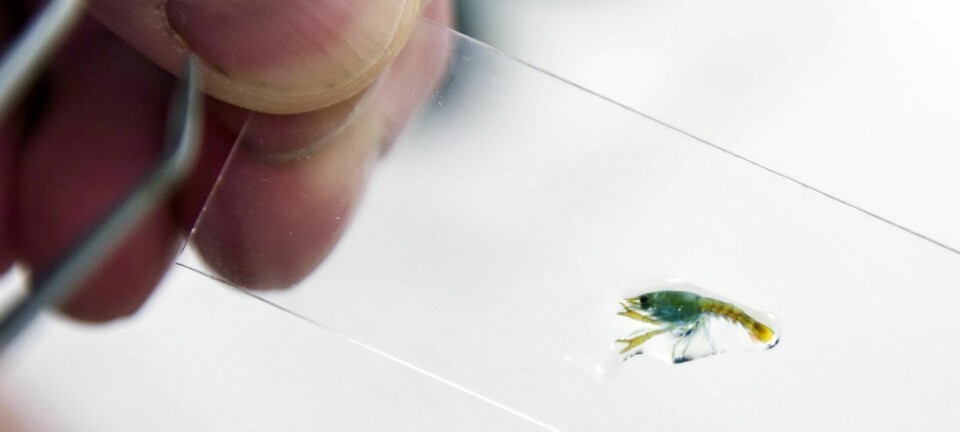

The fake larvae resembled real larvae as much as possible to tempt predators—ants, birds, or mammals—to take a bite before realising the ruse.

After an insect larvae had been attacked, it was carefully collected by the scientists responsible for the area and sent to the University of Helsinki, where two experts analysed the marks made by the predator, independent of each other.

This allowed them to quickly identify whether an ant, a bird, or a mammal was responsible for the attack.

“The good thing about this method is that you can track the predators by inspecting the bite marks. The jaws of an insect, such as an ant, will leave two small holes, whereas a bird will leave wedge-shaped marks. Mammals will leave teeth marks, and so on,” says co-author Eleanor Slade from Oxford University and Lancaster University.

Height also plays a role

When the larvae were collected and analysed, a connection was immediately apparent. The larvae around the tropics were bitten significantly more than larvae closer to the Poles.

It is well known that the tropics contain many more species and a much wider range of biodiversity, and so it might sound very logical that there’s also greater pressure on predators around these areas.

But the results were adjusted for this, which means that the increased species density cannot fully explain the trends.

Moreover the scientists saw another surprising correlation. The pattern was not only horizontal but also vertical—larvae at higher altitudes were less likely to be attacked by predators.

“Biodiversity certainly plays a part in our findings, but it’s probably not the entire explanation. It’s very interesting that we find a parallel pattern across a global gradient, but also along an elevation gradient. It speaks of a joint mechanism,” says Schmidt.

So scientists still do not know why this these trends exist.

“Now, we’ve established the pattern, so the next step is to find the mechanisms behind them. This is where it gets really exciting. When we start to chase after the answer to why it really matters,” says Schmidt.

Trends have long been debated

Professor Kevin J. Gaston who studies biodiversity at Exeter University in England calls the results interesting. He did not take part in the new study.

“It’s an interesting result. The existence of such trends have long been debated,” writes Gaston in an email to ScienceNordic.

He highlights the global scale of the project as one of its strengths, which can be used to reach a deeper understanding of these trends around the world.

“This is a really good demonstration of the power of copying a relatively simple experiment at many different locations around the world,” he writes.

-----------------------------

Read more in the Danish version of this article on Videnskab.dk

Translated by: Catherine Jex