History rewritten: Europeans were “born” in the Bronze Age

DNA from 101 Bronze Age skeletons shows that Europeans came from nomadic tribes who invaded during the Bronze Age.

The biggest DNA study on ancient people rewrites European history. Modern Europeans were born in the Bronze Age after a large wave of immigration by a nomadic people known as Yamnaya who came from the Russian steppe. It happened in the third millennium BC.

"This is where we begin. We see that a large part of the modern European, genetically start here, "says study leader Eske Willerslev, who is a professor at the Centre for GeoGenetics at the Natural History Museum of Denmark.

The find probably marks the end of more than 100 years of archaeological debate over whether the great cultural upheaval seen in the Bronze Age (2700 BC. to 500 BC.) was driven by ideas or by immigration.

"It is completely ground breaking, and the entire history must now be rewritten into a story of mobility and human expansion," says archaeologist Kristian Kristiansen from Gothenburg University. He led the archaeological part of the study.

By extracting and identifying genetic material from 101 Bronze Age people excavated in Europe and Asia, the scientists were able to see who Bronze Age people were and how they were related.

"This is the largest study ever -- more than double that of all previous studies combined -- and for the first time we can make population studies on fossil genetics," says Assistant Professor Morten E. Allentoft from the Centre for GeoGenetics.

The study has just been published in Nature alongside a similar study, led by Professor David Reich from Harvard Medical School, which maps the DNA of 69 Bronze Age people and supports the same conclusions.

Europeans created by three migrations

The last few years were an intense race between Willerslev and Reich to be the first to map and analyse the European’s ancient genetic material.

They have already shown that modern Europeans share the genetic components of the early hunters but with the arrival of farming culture about 8500 years ago, there was a mixing with new genetic components. This shows up as a genetic difference between southern and northern Europe.

Neolithic people (4000-1700 BC) resemble us more but there is still something missing, and last year it became clear to scientists that there must have been a third wave of migration.

This was a migration to northern Europe, which could explain the genetic differences between northern and southern Europeans today.

This is where the new study comes in.

The final piece of the puzzle

It took a huge effort, but Willerslev and colleagues managed to collect bones from all over Central Europe; from Denmark, Germany, Poland, Romania and Italy, and east to Georgia, Russia, and Lake Baikal in Siberia. The age of the bones spanned five millennia, from 6,000 to 900 BC.

"In order to get these 101 samples, we’ve gone through over 600 samples and tested for DNA. All of the samples that could be used have a well-documented archaeological context so we mapped the DNA and dated them," says Allentoft.

The researchers discovered that the early European Bronze Age skeletons had a new genetic component that was not inherited from the early farmers or hunters.

"Whether the sample was taken in Germany, Poland, Denmark or Sweden, we see the same component, and we can show that it comes from the Caucasus," says Allentoft.

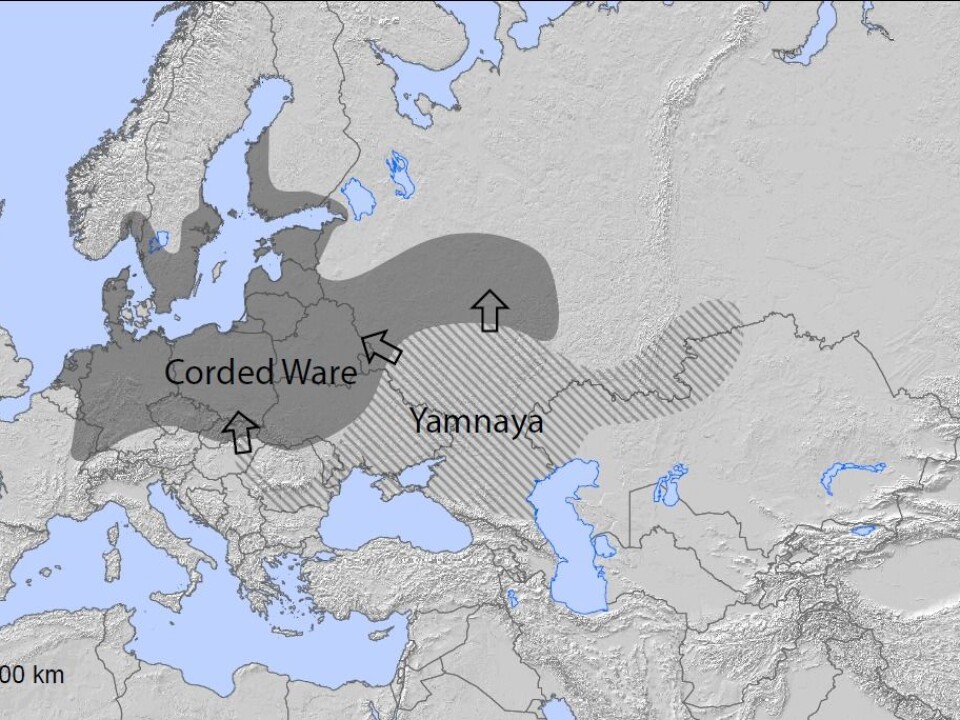

The component matches that of the relatively unknown steppe people, the Yamnaya, who were nomads from thousands of kilometres north of the Caucasus between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea.

Reichs and Willerslev's research groups agree that the Yamnaya tribe migrated west into northern Europe around 5,000 years ago.

Previous archaeological findings have shown that changes occurred in northern Europe around the same time.

The Yamnaya are a landmark ancestor

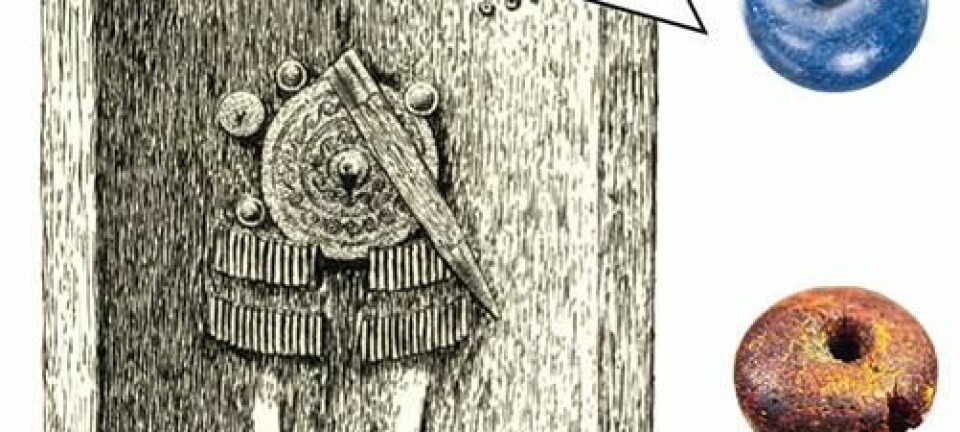

The Yamnaya brought a completely new social structure with them, says Kristiansen.

"Pastoral people are more collective and live in villages, but with [the Yamnaya] there’s a much more individualistic culture, organised in nuclear families. You can see the change in the funeral rituals they introduce, such as the family burial mounds," he says.

The Yamnaya were a nomadic people who brought livestock with them and used horses to pull wagons that carried all their belongings. They burned forests to create grazing land until about 2000 BC when they began to settle down.

"But we see individual households with family farms and not villages," says Kristiansen and points to a fundamental change of Europeans both culturally and genetically.

"They are our main ancestor," he says.

Great upheavals in Asia

Willerslev and colleagues also looked at developments in Asia, which proved to have been much more dramatic than those in Europe.

Here, the first Yamnaya replaced the existing people, and then around 1,000 years later Yamnaya in Central Asia are abruptly replaced by a warlike people called Sintashta.

"They are super warriors who march in and almost completely ‘replace’ the Yamnaya people," says Willerslev.

A much larger group of people from Asia put their descendants under pressure around the end of the Bronze Age. The European genetic profiles become so watered down that ultimately they disappear entirely.

"It's so dynamic and surprising that the Central Asian people we now call native actually are a new phenomenon, and until around 2,000 years ago they were European," says Willerslev.

Solves old conundrum about the origins of Indo-European language

And not only that -- the migration of the Yamnaya culture seems to solve the old conundrum about the origins of Indo-European language.

"The mystery is solved -- the Indo-European language is first spread in Europe and then east to Iran and India," said Kristiansen.

The Yamnaya eastern migration also solves the riddle of how the now extinct Indo-European language Tokaisk arose from within China.

The new study strongly supports the “steppe hypothesis”, which claims that the Indo-European languages spread with these steppe people as late as 3,700 to 2,000 BC.

Why did the Yamnaya people migrate?

With large pieces of the puzzle beginning to fall into place, new questions open up -- such as what triggered that Yamnaya culture to migrate in the first place.

Kristiansen explains the current belief is that there was a decrease in farmers about 100 to 200 years before the Yamnaya migrated. One hypothesis is that these communities were hit by illness or crop failure and famine, which provided space for the Yamnaya.

The new studies set the stage for further work, to map genetic material deeper back in time, as well as our more recent history.

"We can for example see the formation of the modern Dane is not quite complete 2,000 years ago," says Willerslev. "It could be really interesting to see what happens later in the Iron Age and Viking times."

---------------

Read the original story in Danish on Videnskab.dk

Translated by: Catherine Jex