Historic building activity in Europe mirrors plague outbreaks and food prices

A new study shows that the dramatic upheaval and population decline known as the Late Medieval Crisis began much earlier than previously thought. Thanks to the use of felling dates from old construction timber a new picture emerges of past demographic changes in Europe.

During the late Middle Ages, Europe was in crisis. Between half and a third of the population died, and farms and villages were deserted across the continent. But when did this catastrophe, known as the Late Medieval Crisis start?

Were only the Black Death (1346–1353 CE) and subsequent plague outbreaks to blame? Or did it start with the Great Famine (1315–1322 CE) – the worst famine in Europe during the past millennium?

Narrowing down the start of the so-called Late Medieval Crisis has been extremely tricky as the historical sources are patchy and give a contradictory picture of events at this time. Our new study has some answers. It reveals that Europe was already in crisis well before both the famine and the plague.

For the first time, we have reconstructed the history of building activity in Europe from the thirteenth to the seventeenth century using almost 50,000 pieces of precisely dated construction timber from this time. This allowed us to pinpoint a sharp decline in building activity around 1300, which strongly suggests that the Late Medieval Crisis had already started by this time.

The felling dates of the construction timbers reveal a precisely dated history, and represent a new and important piece of evidence that are entirely independent of written records and other types of archaeological evidence.

Read More: Bacterial DNA from the Black Death found in teeth

Tracing people’s activity through their building habits

Variations in building activity reflect demographic, economic, and social change during history. However, there is little documentary evidence for how building activity varied in Europe prior to modern times.

An alternative approach is needed, which is why we investigated the preserved physical evidence for building activity. We reconstructed changes in building activity from the felling dates of construction timbers from archaeological investigations of old buildings.

They are a great, but so far, almost unused resource for studying past demographic changes across Europe. The precise year that the trees were felled can be determined using a technique known as dendrochronology. And as construction typically occurred shortly after a tree was felled, the felling dates accurately reflect the actual time of construction.

Read More: The Black Death came to Europe multiple times

Less building activity during hard times

The entire reconstruction spanned the period from 1250 to 1699 CE. So, once we had established a picture of the variation in building activity in Europe, the next step was to investigate the driving forces behind the changes in building activity.

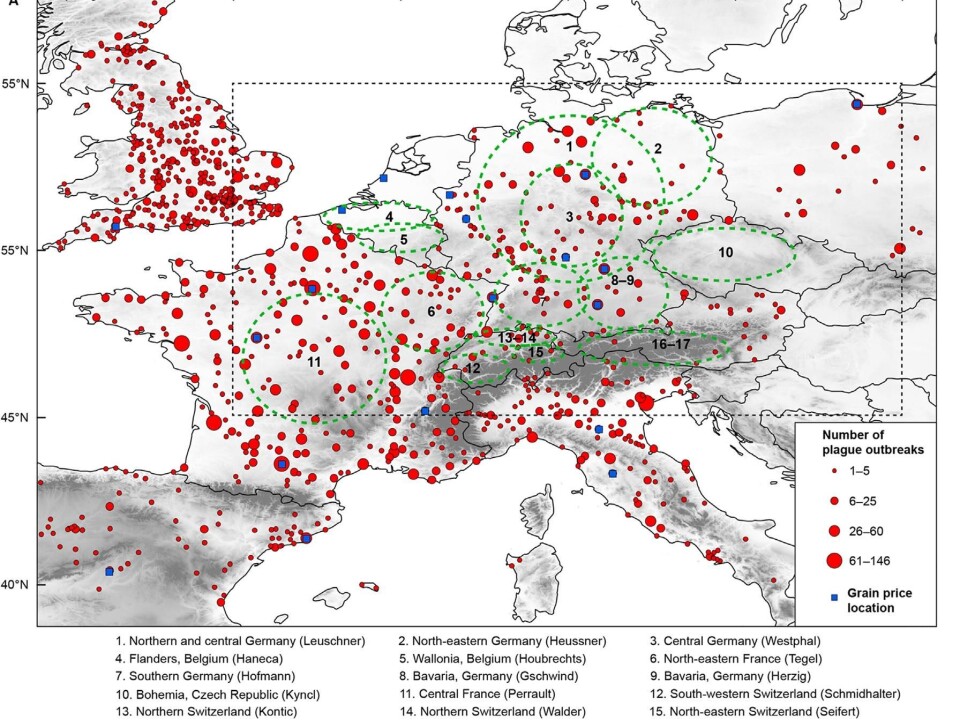

We investigated a range of possible causes but found that the number of plague outbreaks and the level of the food prices had the largest effects.

In fact, the relationship between both the frequency of plague outbreaks and the price of food was remarkably strong; building activity in Europe was lower when plague was widespread or food prices were high. And when there were little or no plague, or food prices were low, people built more.

The largest drop in building activities occurred four to five years after the start of the larger plague epidemics, but just one year later (i.e. within six years of the epidemic onset), building activity had already returned to normal. Clearly, building activity reflects the general level of societal well-being.

Read More: Leprosy DNA extracted from medieval skeletons in Denmark

Unprecedented low building activity during the Thirty Years’ War

We also saw an unprecedented decline in building activity during the devastating Thirty Years’ War (1618–1648 CE).

This decline was most strongly detected in the war-affected regions of present-day Germany. Although historians have long since known that the Thirty Years’ War was the most devastating war on record in central Europe – with a population loss of about a third and regionally as much as 75 per cent – nobody had before quantified the associated decline in building activity.

These new results confirm the construction decline to be about 36 per cent – roughly similar to the population decline caused by the war.

Read More: Evidence uncovered of a 1500-year-old massacre in Sweden

A new historic source material

Reconstructed building activity, based on large collections of felling dates from historic construction timber, is actually a new source material for researchers studying European history.

We found that the felling dates not only cast new light on the timing of the Late Medieval Crisis, they actually reflected demographic, economic and social change in Europe over the entire period of reconstructed building activity.

As the felling dates contain so much valuable information we hope archaeologists and historians will use them in the future now that we have established their usefulness as a historic source. However, this will require archaeologists, historians, and geographers, to collaborate more closely than is typically the case today.

---------------

Read this article in Danish at ForskerZonen, part of Videnskab.dk