Greenland's Iron Age came from space

The basalt on Northern Greenland is visible evidence of the Inuits' use of iron before they had access to modern tools.

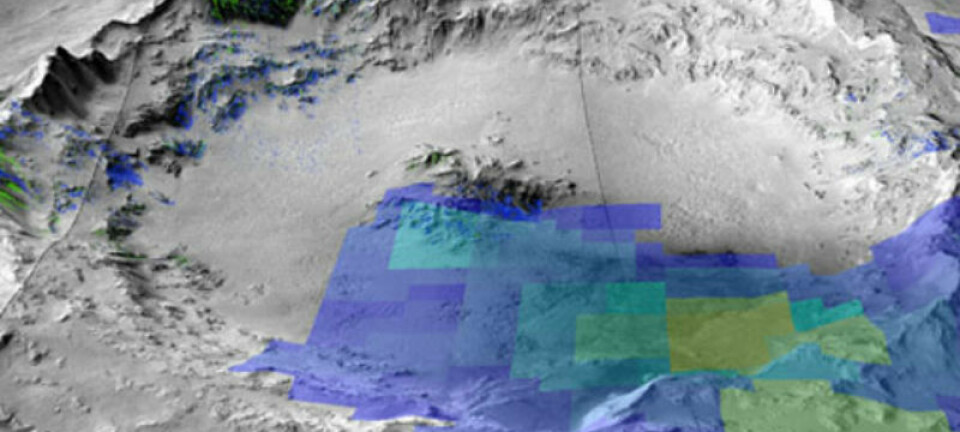

Somewhere between five and ten thousand years ago, a meteorite crashed through the atmosphere over Greenland. On its way through the atmosphere the large lump of rock, several metres across, broke into smaller pieces and was spread across the Greenlandic ice sheet and the sea at Innaanganeq (the Cape York Peninsula) near present-day Thule.

A few thousand years later, the meteorite gave rise to an Iron Age in Greenland -- three hundred years before Icelandic farmers brought iron and agriculture to the south of the world’s largest island.

Since then, practically no archaeologists visited this part of Greenland to examine the locations where the meteor fragments fell or any of the nearby settlements.

That was until August 2014, when a team of geologists and archaeologists landed in the area. The expedition wanted to find and study any traces of humans exploiting the meteorite.

Martin Appelt, an archaeologist from the National Museum of Denmark, was among them.

"We knew the locations because what we have here are large scientific objects. But the story of the meteorites as the whole area's source of iron have sunk into oblivion," says Appelt.

For the archaeologists, he says, it has been a fantastic resource to examine, because the chemical composition of meteoritic iron sets it apart from other types. This made it possible, using the meteoric iron, to establish contacts over huge distances and to assess whether a piece of iron over in Canada came from the Cape York meteorite or some other source.

"This enables us to localise the meteoric iron and see how it has been traded over large distances and testify to the significance of the meteorites from the Thule as a source of iron in the Eastern Arctic.

But the iron had to be processed before it could be traded. This is where the piles of stones come into the picture, because the stones were used as hammers.

"They did a heck of a lot of hammering! The blacksmiths would start by knocking off a small piece, thoroughly beating it flat and giving it a sharp edge, then hardening it further so that it could serve as an arrowhead or flensing knife," says Jens Fog Jensen, archaeologist at the National Museum of Denmark.

Quite an accomplishment

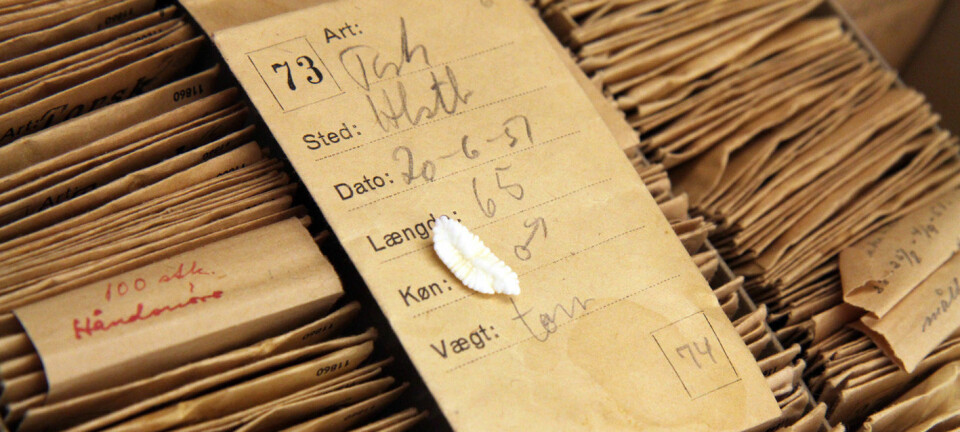

Piles of hammer stones bear witness to the fact that for centuries, people have lugged hammer stones to the iron meteorite when they needed to extract iron to forge a knife or harpoon blade. A specific type of basalt was used, and the size of stone varied from something that could be held in the hand to as much as 40 kg.

They were presumably used as hammers and anvils respectively and exploited until they split.

Mikkel Myrup, an archaeologist from the Greenland National Museum, has measured some of the stones in the piles by drone and estimates the piles may contain up to 70 tonnes of hammer stones -- an estimate Fog Jensen agrees with.

Quite an accomplishment, considering the basalt had to be carried 50 kilometres.

Traces of an iron trade

The archaeologists know that the iron was used from the mid-eighth century by the Dorset people.

When the Inuit arrived in the 12th century, they took over the trade in meteorite iron, which was then spread across an even larger area.

Appelt believes this may be one of the reasons for the disappearance of Dorset people as it contributed to rupturing their social and trading networks.

The meteorite iron was traded as far away as halfway to Alaska. In southern Greenland, in the area occupied by the Norsemen, a single fragment of the meteorite has been found, although the most likely explanation is that it was traded. The Norsemen did not visit the locality themselves.

Stowaway Inuit

The first person to draw European attention to the strange stones at Cape York was an Inuit stowaway. In 1817 the Greenlander, Zakaeus, sneaked aboard a British ship anchored in the Disko Bay.

He reached Scotland and managed to learn English while spending the winter there and eventually e came to the attention of the Arctic explorer John Ross, who in 1818 planned an expedition to the Thule area.

Zakaeus was enlisted as the expedition’s interpreter and was able to help Ross obtain detailed information about the meteorites, place names, tools, and hammer stones.

Others later came by to collect fragments of the meteorites, the larger of which have names. Robert Peary removed Ahnighito (the Tent), Woman and Dog, which can be seen today at the American Museum of Natural History, and Knud Rasmussen took Savik with him to Copenhagen in 1925.

-------------

(This article is reproduced on this site by kind permission of Polarfronten, a Danish online magazine with news about polar research.)

Read the original story in Danish on Videnskab.dk

Translated by: Hugh Matthews