Geology behind mass extermination

New study challenges the established view that a sudden climate change caused a sharp reduction in the number of animal species.

Up to now, a sudden period of global cooling has been seen as causing the destruction of 85 percent of all species on Earth 440 million years ago.

But now Danish researchers say the cause was entirely different – geological processes underground that joined a number of microcontinents together with a larger continent.

“Our study shows that it was not climate change but the location of the continents that determined the number of animal species on Earth,” says Christian Mac Ørum Rasmussen, a postdoc at the Natural History Museum of Denmark (NHM), who carried out the study. “This gives us a completely new view of the current reduction in species, which may very well be due to a similar geological mechanism rather than climate change.”

Mussels tell a story of prehistoric catastrophe

The event Rasmussen refers to occurred at the end of the so-called Ordovician period in the Paleozoic geological era.

The researchers have formed an impression of what happened by mapping the occurrence of one of the most widespread living creatures of the age – a mussel-like animal called brachiopod.

“In the Paleozoic geological era, brachiopods were very prevalent on the ocean beds,” says Rasmussen. “Changes in the number of species of this animal group tell us about the biodiversity that existed at this time in the history of the Earth.”

They found plenty of brachiopod fossils during field work in Greenland, Russia and Scandinavia. Since brachiopods have changed their appearance over time, and many brachiopod fossils have been collected, dated and described in scientific literature, researchers can easily determine when a brachiopod fossil lived.

The fossils collected by Rasmussen and his colleagues were entered in a detailed scientific database that covers the period from 15 million years before the sharp reduction in the number of animal species to 15 million years afterwards.

Islands a wonderland for life

Although there is much talk of global warming today, we are actually in an ice age geologically

Christian Mac Ørum Rasmussen

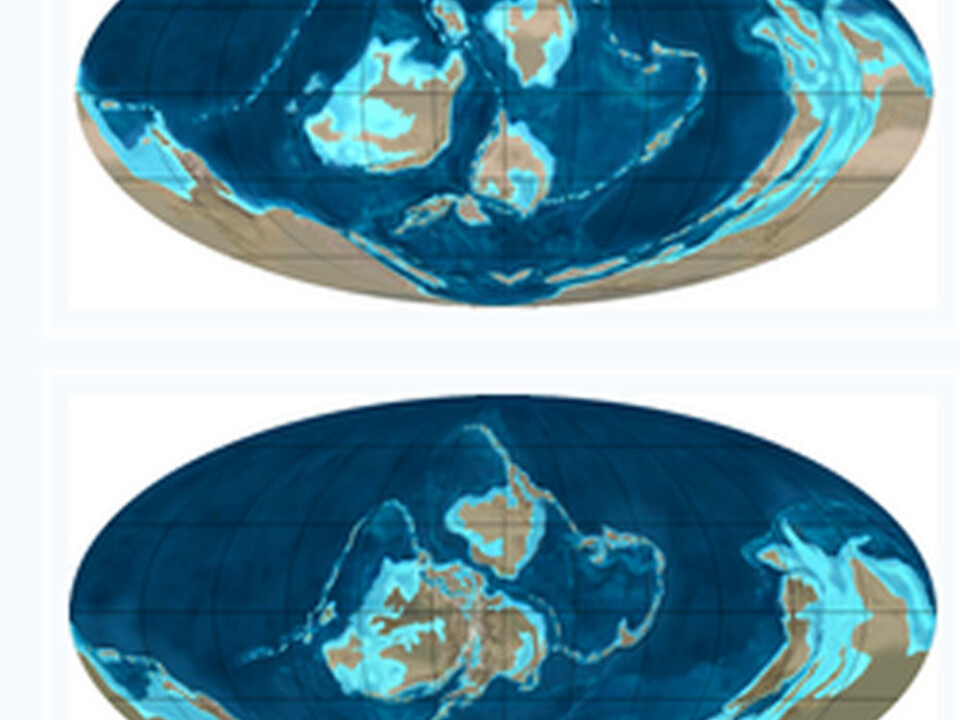

When they started to analyse the many fossils in the database, the researchers discovered to their surprise that the fall in biodiversity was concentrated on small islands (microcontinents) that existed off the coast of a continent called Laurentia – today’s North America – and occurred as geological processes pushed the islands towards and joined them with Laurentia.

The coasts of the microcontinents offered many good habitats for animal life, and the great richness of animals in this wonderland attracted many predators. But these habitats disappeared when the geological forces fused the islands with Laurentia.

The animal life in the microcontinent habitats fought and lost out to the animal life in the habitats on the continental coasts.

“The standard theory was that the acute fall in animal species occurred across the whole globe at that time,” says Rasmussen. “But we can see that the fall took place primarily on islands and this indicates that it was caused by a local geological process rather than a global climate event.”

He adds that a few species adapted to their new living conditions, while most species died out.

“It has taken millions of years for biodiversity to flourish again,” he says.

History repeats itself

During the past 50,000 years, the Earth has seen the sixth-largest fall in the number of species and this catastrophe has many similarities to the mass extinction in the Ordovician period.

The new knowledge is causing the Danish researchers to question whether the fall in the number of animal species that we see today is really due to human activity, as many researchers argue, or to geological processes that are moving the continents.

In the research article, published in Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, Rasmussen and his colleague at the NHM, Professor David A. T. Harper, draw parallels to the current situation and say that the conditions for the two catastrophes are the same.

Today there are many continents in the northern hemisphere – just as there were 440 million years ago.

“Although there is much talk of global warming today, we are actually in an ice age geologically,” says Rasmussen. “We believe the positions of the continents during the ice age may have played a large role in the extinction of the species – a development that was accelerated later by human activity.”

Read the article in Danish at videnskab.dk

Translated by: Michael de Laine