Genes reveal Palaeolithic genders

It can be hard to determine whether ancient human bones stem from a male or a female. Swedish scientists have come up with a gene technology that can help.

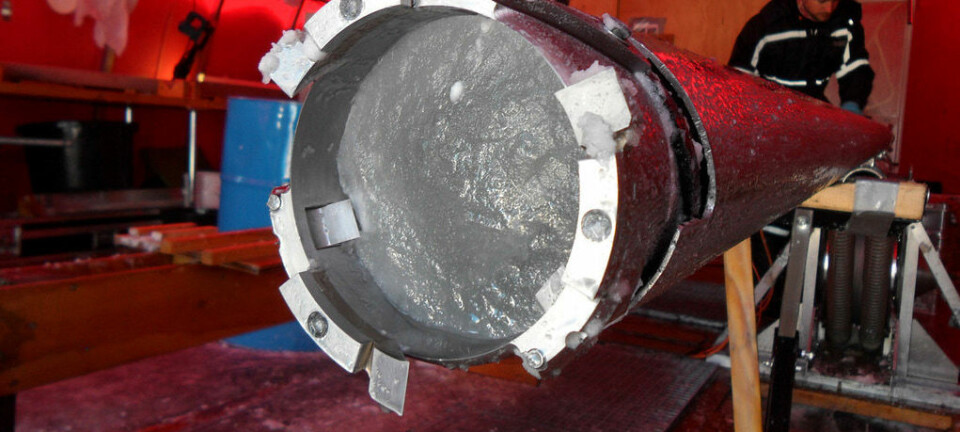

Very, very old human remains - or remains from their ancestors - are rare finds. A well-known example of an old, yet complete modern human is the Ice man Ötzi, the natural mummy of a man who was killed on a glacier in the Alps over 5,000 years ago.

Ötzi was obviously a man. But when human remains are quite old and incomplete, scientists have found it difficult to determine whether they came from a man or a woman. Time has often taken its toll on soft tissues such as genitals or indicators such as facial features, pelvic girth, overall size and the like.

If the individual was a juvenile when he or she died, the skeletal remains will rarely show any differentiation.

Scientists at Uppsala University have come up with a new technique to tackle this problem.

By using an approach called shotgun sequencing, the scientists were able to examine the DNA of 16 individuals and find that the genetic sequences of men and women are distinctly different. The remains dated from as recently as a century ago to as old as 70,000 years ago.

They found out that two Stone Age Scandinavians thought to be women were actually men.

Shotgun sequencing

Gene sequencing involves the mapping of very special organic molecules – adenine, thymine, cytosine and guanine, represented by their first letters A, T, C and G. These form the base pairs of our genes.

A gene is a specifically ordered sequence of such letter combinations, or codes, in our DNA. We have approximately 20,000 genes, so it can take a long time to read through these letter codes, which come in long strands.

Shotgun sequencing gets its name from an analogy to the quasi-random pattern formed by shot fired from a shotgun.

Simply stated, the approach involves isolating and sequencing short individual fragments of lengthy DNA strands. Computers allow scientists to identify matches between samples.

These individual, incomplete puzzle pieces can be fitted together in the proper order, allowing the entire sequence of genetic coding to be determined.

With a lot of work, a whole genome – the entirety of an organism’s hereditary information − can be sequenced.

X and Y specific genes discovered

Pontus Skoglund and colleagues from Sweden’s Uppsala University have used a form of shotgun sequencing to make their discovery.

Their goal was not to read genes, but find and read genes that are only found in our sex chromosomes, X and Y. Women have two X chromosomes and men have an XY combination.

Certain genes are only found on either the X or Y chromosome. Finding these genes would clearly indicate whether the remains of a person are from a man or woman. It’s easiest to determine males, as only they have the Y chromosome.

Females are a little trickier because finding nothing but X genes doesn’t give a sure answer. You might have overlooked or failed to stumble upon a Y gene from the same individual.

But the technique works for women too.

Skoglund and his colleagues analysed the genes of 16 remnants of persons whose sex was already known, including Ötzi, a male Paleo-Eskimo of the Saqqaq Culture on Greenland and a Denisovan female. This last is a ca. 40,000-year-old subspecies of Homo sapiens, so named because her bones were found in the Denisova Cave in Siberia.

When the scientists looked at their results, they found clear differences between the sequences from men and women.

The researchers wrote in the 14 July web edition of the Journal of Archaeological Science that their method is reliable and can contribute new insights.

Swedish Stone Age woman was actually a man

Skoglund and fellow researchers found that their genetic analysis also worked for the six Neanderthals they investigated. This means the method is not strictly limited to determining the gender of Homo sapiens.

The goal of the study was not to determine the sex of newly discovered material from archaeological digs, but rather to test whether the method was dependable. So the scientists weren't expecting new revelations about the test subjects.

But they were in for a couple of surprises.

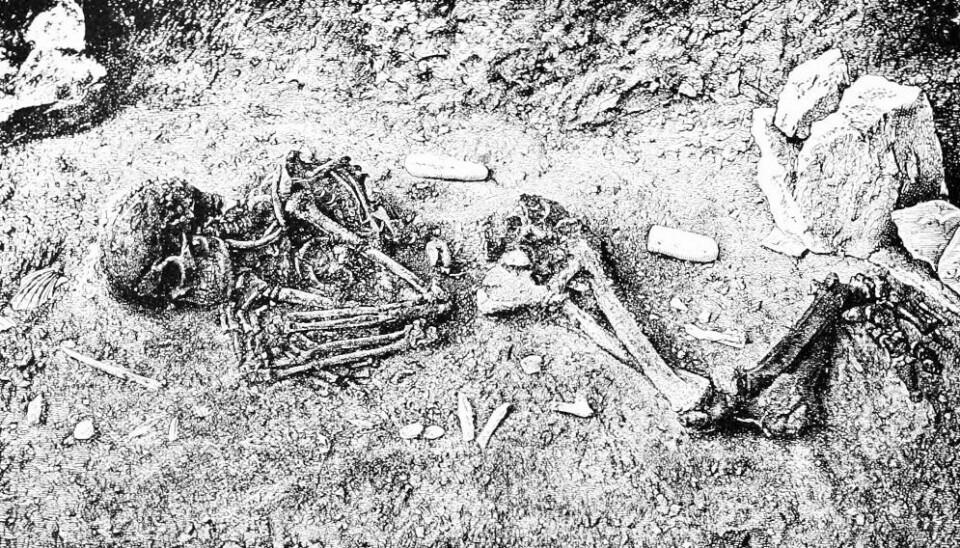

Two individuals from the Swedish Pitted Ware Culture – hunter gatherers from Scandinavia who lived around 4,000 years ago – had been thought to be women. Just the skull of one had been found − at Ire on the Baltic island of Gotland. The other, from Gökhem in Sweden’s Västra Götaland County, was only known from a jaw bone.

The shapes of the two bones had led scientists to believe they were from prehistoric women. But the DNA shotgun sequencing showed them to be males.

Info about prehistoric cultures

Determining the sex of ancient human remains can be very useful. Theories archaeologists have about ancient societies, their cultures, social roles, religious practices and more can be linked to the gender of individuals who are excavated or found in specific positions or circumstances, or perhaps buried along with certain objects and symbols.

The researchers write that the Gökhem man was young when he died. As we all know, the sexual differentiation between males and females grows much more discernible at puberty.

So even if a more complete skeleton had been found, it’s uncertain whether its sex would have been determined prior to the advent of the new technique.

The scientists point out that their approach will be of value in cases where gender is hard to determine, when the remains are fragmentary or stem from juveniles.

------------------------

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no

Translated by: Glenn Ostling