Football saves the bones of prostate cancer patients

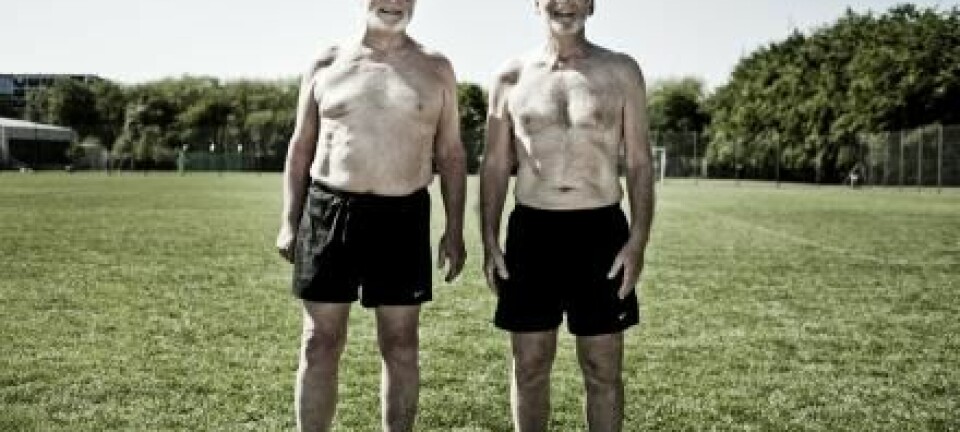

Men with prostate cancer are at risk of developing osteoporosis, but this can be avoided with 32 weeks of football training.

Football or soccer if you prefer, is not just good for the heart and muscles. Sprinting, jumping, turning, and generally kicking a ball about on the turf can also strengthen your bones.

Even older men undergoing treatment for prostate cancer, will have stronger bones after playing soccer, according to a PhD dissertation by physiotherapist Jacob Uth from University Hospitals Centre of Health Research (UCSF), Copenhagen, Denmark.

The results may come as a surprise, as men with prostate cancer normally have weaker bones after taking anti-hormone treatments as part of their overall cancer treatment.

Soft bones increase the risk of developing osteoporosis and fractures.

"Soccer counteracts several side effects of the treatment,” says Peter Krustrup, professor at the Institute of Sports Science and Nutrition at the University of Copenhagen, Denmark--supervisor on the project.

“It’s impressive that there’s such a large and systematic improvement in both muscle strength and bone density considering that the group consists of older and relatively weak men who are in treatment," he says.

Football works better than strength training

Krustrup was part of an earlier research project called FC Prostate--a football team made up of men suffering from prostate cancer--which showed that the men would develop larger and stronger muscles by playing football.

The FC Prostate players also took part in the new study.

In healthy people, it is well known that exercise is good for the bones, but very few studies have examined the effect in patients with prostate cancer.

The few studies that do exist have looked at more traditional forms of exercise such as weight training exercises and jumping on the spot, and have found no significant relationship between these exercises and healthier bones.

"So far no one has managed to demonstrate that exercise can improve bone health in male prostate cancer patients receiving hormone treatment. So we think that it’s particularly interesting that we’ve been able to increase their bone mineral density with football," says Uth.

The study is described in two scientific articles, published in the European Journal of Applied Physiology and the journal Osteoporosis International.

Bones appear 2 to 4 years younger

In the FC Prostate Project, 29 male cancer patients played soccer 2 to 3 times a week. A similar control group did not play football.

After 12 weeks, the football players’ leg bone-mass had increased, whilst bone mass in the rest of the body was maintained. Uth also found an increase in biological markers of bone growth in the players' blood.

During the same period in the control group, the men lost leg bone-mass, whilst their levels of biological markers of bone growth were unchanged.

After 32 weeks, the soccer players had significantly increased bone mineral density of the hip and the upper part of the femur, and their bones appeared up to two to four years younger.

"It’s interesting to see that physical training with football makes this difference,” says bone researcher Peter Schwarz, head of the Research Centre for Aging and Osteoporosis at the National Hospital and clinical professor at the Department of Clinical Medicine at the University of Copenhagen, Denmark.

“It’s to be expected, but it’s not been documented before, so it’s very good data that they present here. And it’s great that they see such a good result after 12 weeks of training,” says Schwarz, who was not involved in the study.

Stop-start makes football so effective

The players' movements were measured carefully with GPS throughout their football training. Whilst their average speed was relatively low, the stop-start action of football--running for the ball and stopping suddenly--may explain why it was so effective.

Bone growth is stimulated when the muscles around the bones contract--such as when you land on a surface and a shock is sent up through the bones, says Uth.

"The bones are most stimulated when there is movement in many different directions. So changing direction a lot, kicking, and resisting an opponent while playing football all provide a wide range of powerful stimuli on the bone," he says.

The downside: Some players were injured

But can this training have any negative side effects? Out of the 29 players, three suffered from muscle tendon injuries, and two suffered bone fractures during the training. But the injured players did not require any surgery, and three of them returned to training.

"It's a double-edged sword. Bone health in the football group improved in clinically important areas such as the upper femur, but this should be weighed against the risk of injury in a small number of participants," says Uth.

The scientists believe that the long-term positive effects of the football training outweigh this risk of injury. As many of the players continued their training after the trial without suffering any fractures.

-----------

Read the Danish version of this article on Videnskab.dk

Translated by: Catherine Jex