Eels can escape the Mediterranean Sea

Electronic tags reveal that eels can and do make it out of the Mediterranean Sea to reach their breeding grounds in the Atlantic.

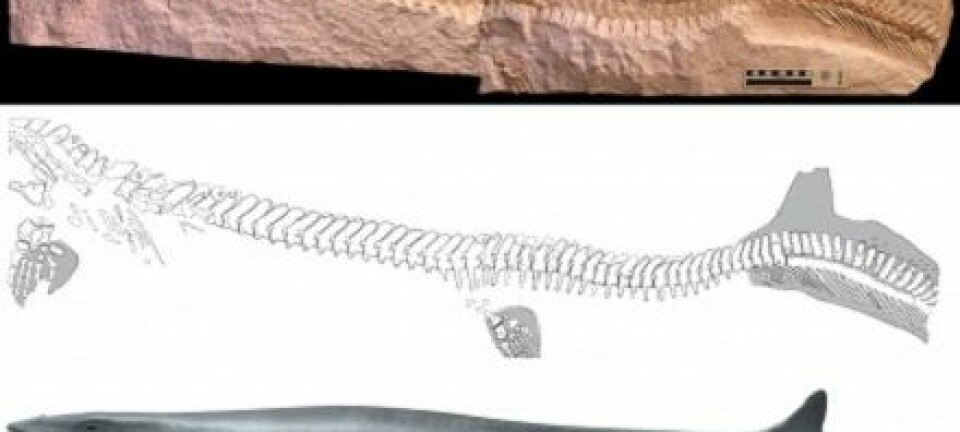

Every year, the European eel migrates to the Sargasso Sea in the Atlantic Ocean to breed. This journey is an important one as eel stocks continue to decline year on year. But we know surprisingly little about this journey.

One hypothesis is that European eels in the Mediterranean do not take part in this trip at all. They simply cannot find their way out through the narrow Strait of Gibraltar to reach the Atlantic Ocean. Unable to migrate and breed, this could prompt arguments against their conservation.

Now there is a new hypothesis. Using electronic tagging to track Mediterranean eels, scientists have evidence that some of the eels do indeed make it out of the Mediterranean and into the Atlantic Ocean.

We should not give up on this population just yet, say the scientists.

“Mediterranean countries should help save the eel. We cannot write off the area in terms of the conservation of this population," says co-author Kim Aarestrup, senior researcher at Danish Technical University (DTU).

The study is published in the scientific journal Scientific Reports.

Mediterranean Sea disrupts eel navigation

The relatively high rates of evaporation in the Mediterranean were suggested to cause problems for eel navigation, preventing them from leaving the Mediterranean.

Eels navigate using changes in sea temperature and salt. The Mediterranean is both warmer and saltier than the Atlantic, and as you approach the narrow straight of Gibraltar the water becomes saltier and warmer. This confuses the eels, and makes it difficult for them to find their way out to the Atlantic.

Consequences for eel conservation

All EU countries with migrating populations of eels are obligated to conserve them. But some suggest that there is no point in protecting Mediterranean populations if they are not migrating to breed.

"It can be used as a political argument. Mediterranean countries can say that they cannot do anything because the Mediterranean is an ecological trap," says Aarestrup.

But the new study suggests that Mediterranean eels do indeed exit through the Strait of Gibraltar.

Eel tracking confirms exit from Mediterranean

In 2009, scientists used a new digital tracker to follow the eel movements.

"We've never caught an eel egg or observed adult eels in the Sargasso Sea. We simply haven’t caught them at ‘the crime scene’ to describe what's going on. So we [followed] the adult eels to the Sargasso Sea," says Aarestrup.

Aarestrup and his colleagues put so-called pop-up satellite tags on the back of eight eels in the Mediterranean. The tags store information about depth, sound, and temperature and are programmed to detach from the eel after six months. At this point, they float to the surface of the ocean and transmit their data to the ARGOS satellite, which the researchers can then download.

They saw that five of the eels were likely eaten, one was still in the Mediterranean, but two had reached the Atlantic Ocean.

"We can confirm that two of the three who survived, had come out [of the Mediterranean],” says Aarestrup. “So it’s certainly not true that they don’t find their way out."

"Very clear results"

But are two successful exits enough to confirm that eels can indeed leave the Mediterranean to breed in the Sargasso Sea?

Professor Michael Møller Hansen thinks that it is and describes the results as “convincing.”

Hansen was not involved in the study, but he studies evolutionary biology and population genetics among eels at the Department of Bioscience, Aarhus University, Denmark.

"Virtually all of the eels that didn’t come out [into the Atlantic] were eaten. So the study makes sense and disproves the theory of the Mediterranean [trap]," says Hansen.

He thinks the "very clear results" will help biologists to study the behaviour of other species of fish in the Mediterranean.

"The Mediterranean is a very special area. The Strait of Gibraltar is a barrier for many species of fish and populations of fish inside and outside the Mediterranean are often genetically very different. It’s therefore clearly relevant to find out how different fish behave in relation to this barrier,” says Hansen.

---------------

Read the Danish version of this story on Videnskab.dk

Translated by: Catherine Jex