Did Stone Age people build a large labyrinth in Denmark?

Archaeologists have discovered a large enclosure from the Neolithic period near Stevns in Denmark--but the purpose of the site is a mystery.

A series of Stone Age palisade enclosures have been discovered in Denmark in recent years and archaeologists are still wondering what they were used for.

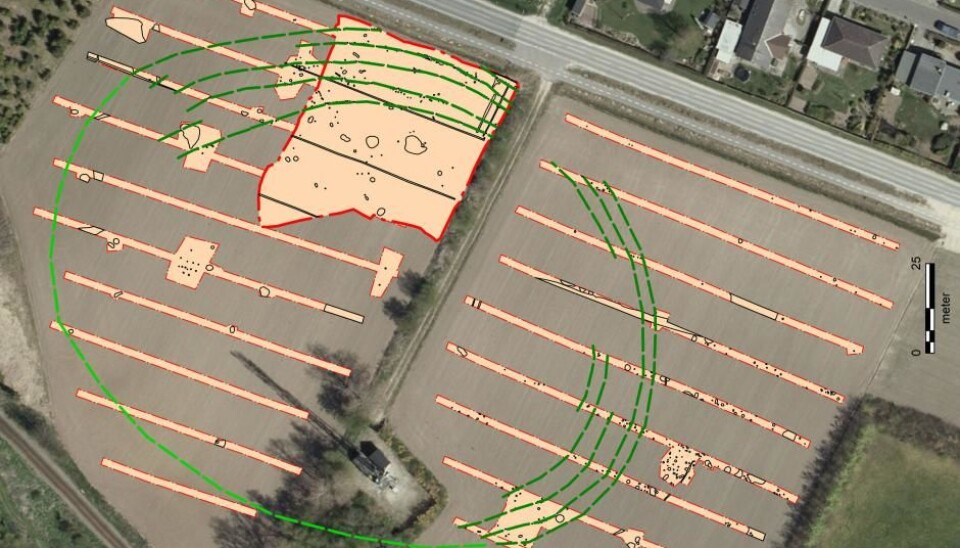

One of the latest additions is a huge construction, discovered by archaeologists from the Museum Southeast Denmark. The fence dates from the Neolithic period and seems to frame an oval area of nearly 18,000 square meters.

“It was actually somewhat overwhelming to experience that it is possible to reveal the traces of such a huge building from the Neolithic period. There are many suggestions for what they could’ve been used for, but to put it simply, we just don’t know,” says archaeologist Pernille Rohde Sloth who leads the excavation.

Read More: Viking fortress in Denmark stumps archaeologists

What was the space used for?

One of the most remarkable things about the fencing at Stevns is the way the entrances have been constructed. The fence is in fact built in five rows that extend outwards, and the opening in each row appears to be offset from the others.

Sloth suspects the uneven design was deliberate.

“The openings don’t seem to sit next to each of the post rows, and we're slightly amazed by that. But maybe it functioned as a sort of labyrinth--at least that’s how we imagine it. That way you weren’t able to look inside the common space, which may have been an advantage,” she says.

But what was going on inside the enclosure that was so secret?

Archaeologists have not yet found any structures or construction in the area that could point them towards any possible purpose for the enclosure.

So far, they have only discovered single pits of various sizes containing flint tools, waste, and some ceramic fragments.

“A palisade construction is typically built for protection, but we don’t think that that is what the construction at Stevns is. The rows of poles would have been around two metres high and weren’t very close together, so you could probably squeeze through them if you wanted to. We believe that it was some kind of fenced gathering area, but it’s difficult to say what it was used for,” says Sloth.

Read More: Archaeologists discover a Viking toolbox

Stevns is far from alone

The archaeologists have not been able to excavate the whole area. The excavation is happening alongside the construction of a new sports hall and there could be many secrets hidden away in this unexplored area.

Stevns is not the only excavation to run up against this problem.

“A number of palisade enclosures have been identified in recent years. So far, we’ve found most in East Zealand [in Denmark], but also on Bornholm and in Skåne [Sweden], and possible also in Falster [south east Denmark],” says Sloth.

“We’ve got bits and pieces from the excavations because we typically discover them in connection with building projects, but as an archaeologist we need to think about and connect the available information,” she says.

Read More: Stone Age artists used rock art as a billboard

“It must have enclosed something”

Some of the most interesting palisade sites are found on the Danish island of Bornholm in the Baltic Sea.

Archaeologists discovered a large palisade built of timber on Vasagårds Field on the southern part of the island in 1988. In the middle of the enclosure, they discovered a so-called sun temple containing various sun symbols.

A similar temple was discovered elsewhere on the island. It may be that these sun temples only exist on Bornholm, but head archaeologist at the Bornholm Museum, Finn Ole Sonne Nielsen, does not rule out that the enclosure at Stevns could contain similar finds.

“It could well have had a ritual purpose. What’s really exciting about this place is whether [they] find something else in the enclosure similar to our Bornholm discoveries. It would not surprise me if it was a temple area. It would have enclosed something and I think that these temples were much more widespread than we tend to believe,” says Nielsen.

Read More: Archaeological discovery in Sweden reveals site of Stone Age rituals

Older installations could be predecessors

Nielsen emphasises that there is a difference between the Bornholm palisades and the “new” construction discovered at Stevns. For example, the poles are located much closer together in Bornholm, which was probably built before Stevns.

Sloth is still waiting for precise dates on the Stevns site, but some of the scraps of broken pottery found on site suggest that it could date to the latter part of the Middle Neolithic Funnel Beaker Culture from 2900 BCE to 2800 BCE. The Bornholm sites are even older.

“We’ve unfortunately not found any circular shaped constructions like they have on Bornholm, but the similarities between the enclosures makes me think about rituals in our finds too,” she says.

With no further funding to excavate the rest of the site, it is difficult to know whether for example there ever was a sun temple on the site.

But Sloth and her colleagues already have a lot of work to do before they can find some more answers to this mysterious site.

---------------------

Read more in the Danish version of this article on Videnskab.dk

Translated by: Catherine Jex