Denmark’s past viewed from above

There’s a lot to learn about the past by studying the land from high above. See a series of stunning aerial archaeology photos here.

Since 2009 archaeologists have been using small aircraft to map nine areas in Denmark that are of particular interest to archaeologists and historians.

The project is called 'The past as viewed from the sky – air archaeology in Denmark' and will initially run until 2013.

But what can aerial photos possibly tell us about the past?

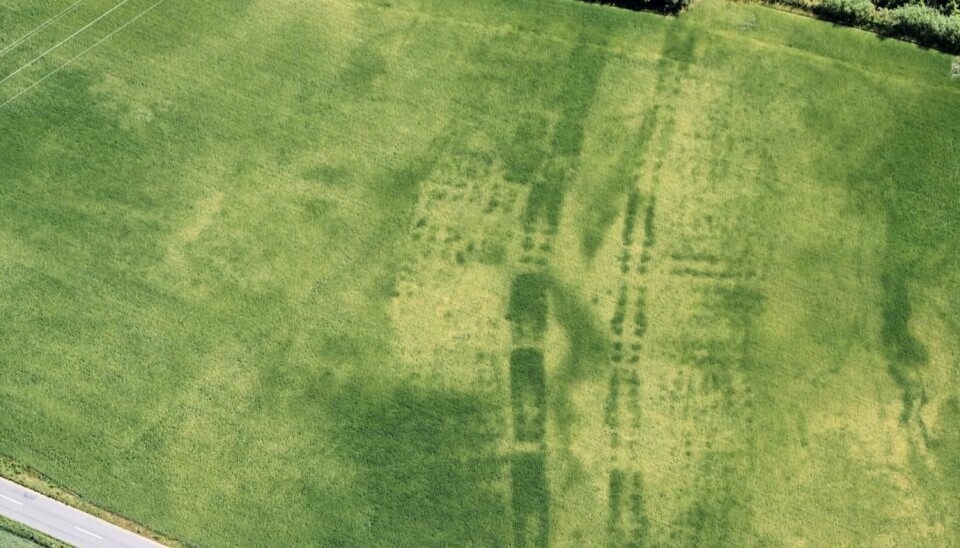

Quite a lot, actually. When, for instance, the Vikings dug deep holes for the poles that bore their houses, it significantly altered the growth conditions on that particular piece of land.

This means that it’s still possible to spot differences in the way the grain grows on just the circle of land where the pole once stood.

This helps archaeologists determine the nature and the age of the buildings and the settlements.

“The objective of this project is to gain a clearer view of the ancient monuments in Denmark. I hope this will spark a greater interest in the past,” says archaeologist and project manager Lis Helles Olesen, who is also a curator at Holstebro Museum.

Sand is ideal for aerial archaeology

There are great differences in the kinds of soil layer that the archaeologists study from above. And that’s actually part of the reason why just these nine areas were selected: they represent all types of soil layer.

The objective of this project is to gain a clearer view of the ancient monuments in Denmark. I hope this will spark a greater interest in the past.

“Sandy soil is the most suitable for studying archaeology from above,” says Olesen. “This is because growth differences in the soil layers are greater in sand than in other soil types, and that makes it easier to spot differences in the crops.”

Corn is better than grass, but grass is better than both potato and maize fields.

There may also be great differences in the appearance of the fields from year to year. During a very dry summer, archaeologists can make plenty of good, previously undiscovered finds by circling around the fields.

On a wet summer, however, the number of finds is much more limited. The corn simply grows too well, which means that growth differences in the grains are not sufficiently large for the archaeologists.

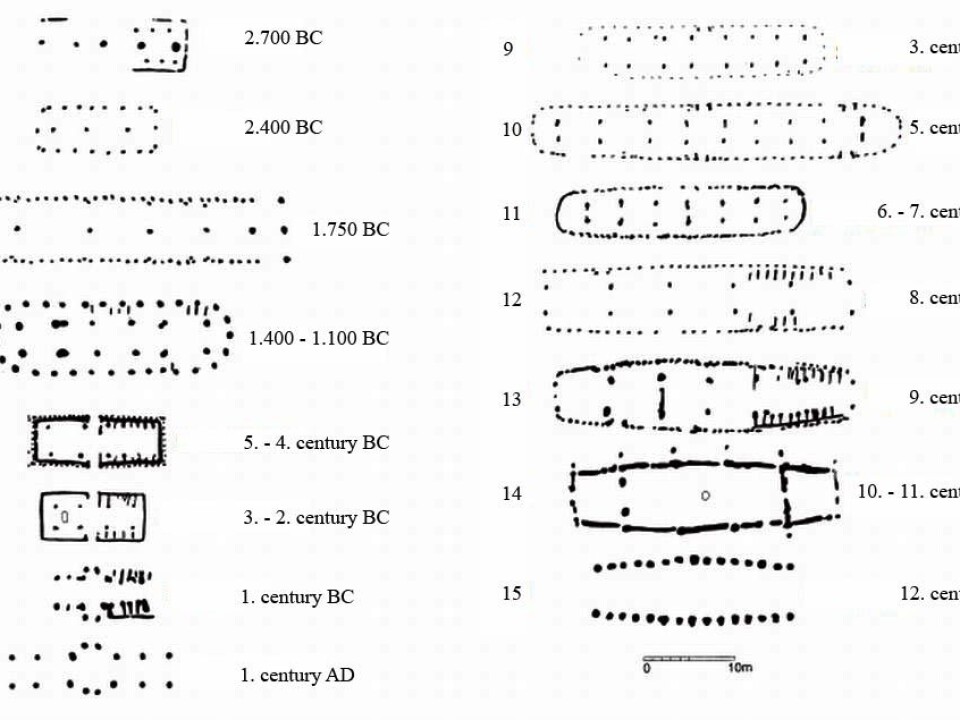

The houses change appearance throughout antiquity, and archaeologists now have a good overview of how the houses have looked in various periods of history.

Other factors such as humidity and light can also influence how much or how little is visible on a given day.

For that reason, archaeologists sometimes keep coming across new finds simply by flying back and forth over the same piece of field at different times.

Ancient houses can be used to date findings

Of particular interest to the aerial archaeologists are remnant houses – houses that people once lived in. These houses enable archaeologists to determine with great precision which time period the find dates back to.

“The houses change appearance throughout antiquity, and archaeologists now have a good overview of how the houses have looked in various periods of history,” she says.

”The most characteristic ones are the remnant houses with curved walls from the Viking Age [picture 5]. The design allowed for a minimum of poles inside the house to hold the roof. This opened up for a big open space in the middle of the house, in which large groups of people could be brought together.”

One of the most common finds in aerial archaeology is 'pit houses' – labour huts from the Viking period (picture 3). They were dug no more than a metre down into the ground. This makes it very clear to see that the grains grow differently in these areas.

Old photos scrutinised

However, 'The past as viewed from the sky – air archaeology in Denmark' covers more than the flights, which only take place in the summer.

The researchers also put old photos under systematic scrutiny – as with, for instance, photos taken during World War 2 to map the land.

Although the old photos are taken at a very long distance, they could well contain secrets from the past.

So far, the project has revealed more than 2,500 sites that may be of archaeological interest, and which could result in further funding for the project.

Olesen sincerely hopes the project can continue past its scheduled expiration in 2013.

Photo credits: Lis Helles Olesen and Esben Schlosser Mauritsen

Translated by: Dann Vinther