Climate change is destroying Greenland’s earliest history

Rising temperatures and heat producing bacteria threaten the remains of three major Greenlandic cultures preserved in the permafrost.

The frozen ground around Ilulissat Ice Fjord in western Greenland is a treasure trove for archaeologists.

The permafrost in this area, which is on the UNESCO World Heritage list, acts like a giant freezer, preserving the remains of the three major cultures of Greenland’s past in deposits known as kitchen middens -- essentially ancient dunghills created by the early cultures on Greenland.

These are the Saqqaq, Dorset and Thule peoples, who at various times in the last 3500 years all lived in the old settlement of Qajaa, in south Greenland.

The middens of these three cultures developed over time as layer upon layer of ancient household waste, and are now preserved in the vast arctic permafrost.

Archaeologists working at the Qajaa site have found traces of DNA and excavated hundreds of tools of wood and bone that are uniquely preserved in the permafrost.

However, scientists now predict that in 80-100 years, these unique archaeological deposits could entirely disintegrate, and the secrets of these ancient cultures could be lost forever. These are the findings of a team of researchers who have just published their results in Nature Climate Change.

According to Professor Bo Elberling, who heads the Center for Permafrost at the University of Copenhagen, this 3500-year record of population immigration and daily life in West Greenland is exceptionally well preserved -- however, these vast regions of frozen ground are now threatened.

Bacteria accelerates midden destruction

Elberling and his team, including colleagues from the National Museum of Denmark, drilled into the frozen layers of soil in Qajaa and at five other places around Greenland. Back in the laboratory they looked for signs of heat production in the soil.

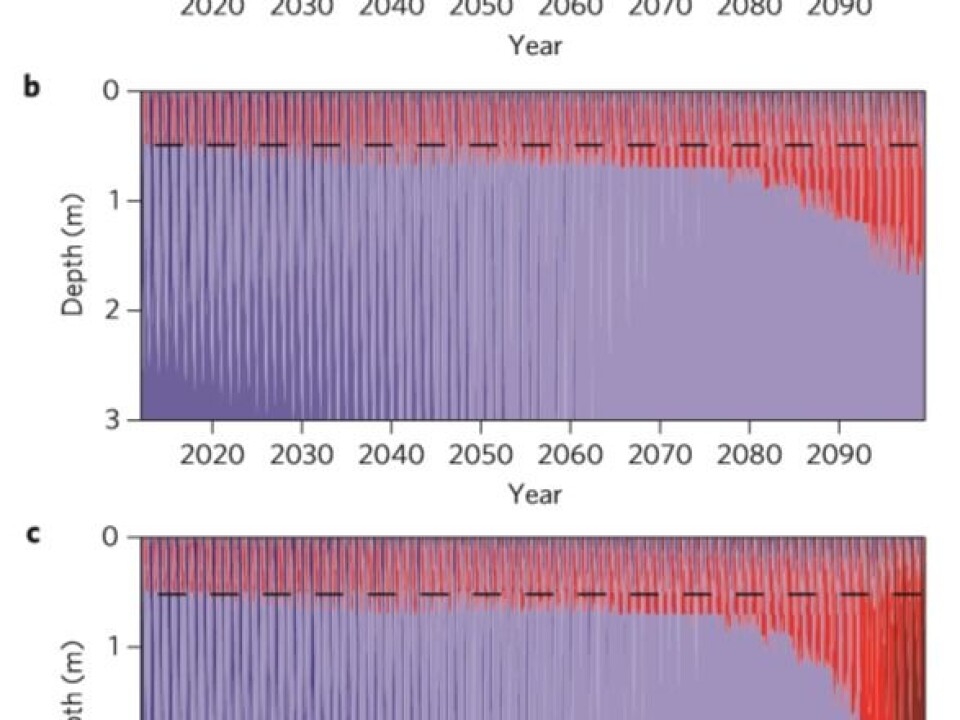

Using computer models, they then predicted how global warming is likely to affect the temperature, water content, and the amount of bacterial activity in the soils.

They discovered that bacteria in the permafrost could accelerate a process which could lead to the complete degradation of the kitchen midden deposits.

They found that soil in permafrost regions has been gradually heating up due to the atmospheric warming of the last 20 years and that bacteria, that until now have been dormant in the permafrost, have awakened and become active.

These active bacteria produce heat, causing the soil to heat up even more, and thaw even faster. Scientists call this a positive feedback.

When the ice melts and the water drains away, it allows oxygen into the defrosted soil-layers. This causes them to quickly degrade.

As the bacteria eat away at the organic residues, everything in the midden deposits -- except the remnants of stone tools -- is eventually destroyed. This includes traces of ancient DNA and all artefacts made of organic material such as wood or bone.

Archaeologists bemoan the loss of ancient sites

The worst case scenario, says the researchers, is that the midden deposits may become so hot that they in about 80-100 years reach what researchers call a tipping-point.

"We reach the point where the entire deposit -- no matter what’s happening to the climate -- warms up, and the heat generated internally becomes large enough to cause it to thaw," says Elberling. “When the ice melts and the water is drained, there’s no way back.”

This is bad news for archaeologists.

"If these ancient deposits disintegrate or otherwise become damaged it’ll be a great archaeological loss -- it would be very sad," says Jens Fog Jensen, a senior researcher from the National Museum of Denmark.

“The only settlements we know of, where the conditions required for preservation of wood, bone, hair, and all other types of organic material left behind in the permafrost are met, are those in Greenland," says Jensen.

Cultural heritage can be saved

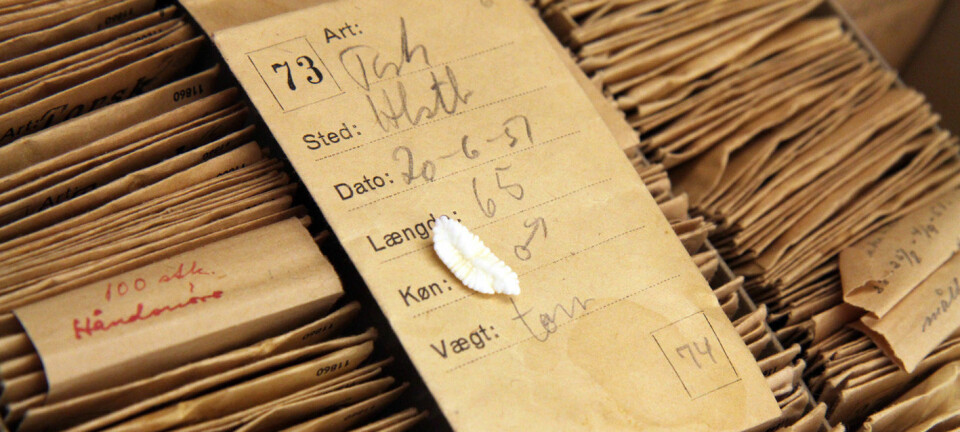

Jensen has studied hundreds of wooden and bone objects excavated from Qajaa in the 1980s and believes that all is not yet lost.

Amongst the midden remains he has found arrows, hafted knives, spears, sewing needles, and many other objects which are not usually preserved outside of permafrost regions and have only been found in a handful of settlements.

“This is where we can learn about material culture, which otherwise is not considered at Stone Age settlements where only stone is preserved" says Jensen.

He points out that the tipping-point in midden degradation is not predicted until the end of the century so there is still time to save this vital part of the country's cultural heritage.

"You can excavate the middens and you can of course also make all kinds of weird installations where you artificially freeze it or otherwise ensure that it gets a more stable climate," says Jensen.

Not only an archaeological issue

It is not only midden in Qajaa that will be affected if these bacteria wake up and start producing heat in the otherwise frozen ground. The researchers also studied permafrost soils at five other sites in Greenland and found that they too are warming.

The large amount of organic material held in these soils represents a large source of carbon. If the permafrost melts, much of this will be released into the atmosphere as CO2.

Right now, this process is not included in climate models and it leaves an open question as to how such rapid thawing of permafrost may affect future climate.

"If the heat we’ve measured is representative of much of the Arctic -- for example the large wetlands in Russia which store large amounts of carbon -- then the internal heat may be of great importance for the release of carbon dioxide and methane. We just don’t know how much," says Elberling.

The debate continues as to how and when these greenhouse gases may be released into the atmosphere. Many suggest it will happen all at once, a sort of giant carbon bomb, once the permafrost has reached the tipping-point.

However, a new study by Alaskan researchers which was published in Nature earlier this week, suggests that melting permafrost is likely to cause a gradual and prolonged release of CO2. Whatever happens, permafrost soils contain twice as much carbon as there is currently in the atmosphere so these questions need answers.

The scientists are now investigating heat production in the permafrost in Canada and Siberia to find out if it is similar to that in Greenland.

Ultimately, their findings will be included in a regional climate model that will provide more answers as to how and if the heat production by bacteria in permafrost could affect the climate in the future.

-------------

Read the original article in Danish on Videnskab.dk

Translated by: Catherine Jex