Chimpanzee hands and feet amputated by snares

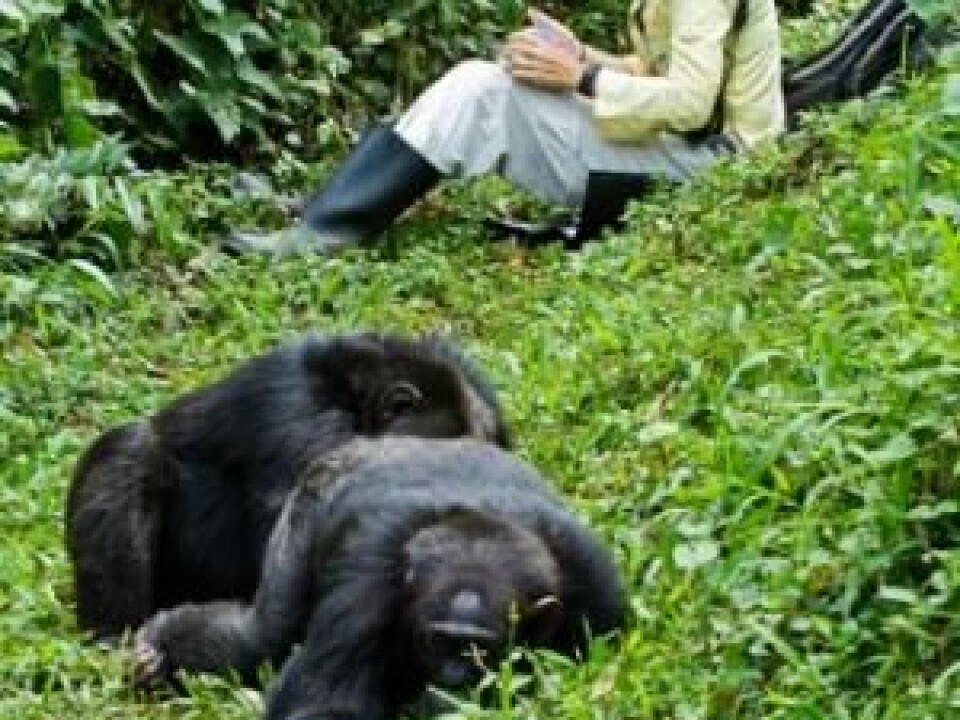

Snares have wounded almost half the chimpanzees in a Ugandan national park. Scientists investigate how this affects the chimps’ lives.

By the time he was eight years old, Max had lost both his feet.

The chimp, who lives in the Kibale National Park in Uganda, got caught on two separate occasions in snares set in their thousands by trappers in the national park.

Snares consist of string or wire, which gradually eat into the flesh of an animal that, in a state of panic, is desperately trying to get free. Today Max has only stumps at the ends of his legs.

"Max has lived without feet for almost ten years. It’s incredible that he survived at all. You always see him in the periphery of the group of chimps, and when they move on he's always well behind the others," says Jessica Hartel, a post-doctoral researcher at Aarhus University in Denmark.

In her research she is examining how snare injuries impact on the lives of the chimps, while at the same time leading the 'Kibale Snare Removal Programme' -- endeavouring to rid the Kibale National Park of snares.

The forest equivalent of land mines

The job of removing the snares is, however, far from straightforward. According to Hartel, there are some 15,000 snares in the Kibale forests at any one time and although the snares are intended for small animals, many chimps are caught in the primitive traps.

"It's estimated that about a third of Uganda's chimpanzees have been injured by snares,” says Hartel.

“But I think the problem is bigger than that, certainly in the Kibale National Park. Our colleagues have set up cameras in the forests, where we can see that around half the wild chimps have been injured by snares. It's really scary," she says.

She too has been caught in snares in the Kibale forests, which like land mines can be difficult to see.

"It hurts, but we humans have the advantage that we can take a snare off. Chimps and other animals panic, however, and don't try to release themselves. They simply tighten the snare every time they try to pull themselves free,” she says.

“We often find that the snare has cut its way deep into the flesh and cut off the blood circulation. And ultimately, the finger, foot, or hand falls off," says Hartel.

Researcher: A pervasive problem

Martin Reinhardt Nielsen from the Department of Food and Resource Economics at the University of Copenhagen, Denmark, studies trapping and poaching in a number of countries in Africa. He agrees that snares are a huge, pervasive problem for local fauna.

"In some places the ground is overrun with traps -- there's barely a rat hole without a trap," he says.

"They're usually set by poor local inhabitants to catch small antelopes or something else to eat. But it's very common for large primates to be caught. Unlike antelopes, they are usually so big and strong that they can tear themselves away and survive. But they sustain major wounds and some of them lose a hand or a foot," says Nielsen.

Snares can cause social downfall

Nielsen points out that chimpanzees are intelligent animals that live in social groups. When a chimp is caught in a snare, the damage may not only be a physical injury, but they will also lose their status in the group.

"I've seen chimps in Uganda sitting there without hands leading miserable lives. When a chimp is injured, the others exploit the opportunity to push them down the hierarchy. I remember one chimp in particular, who had lost a hand in a snare. Because it had become weak, other apes then tore its eye out," says Nielsen.

In her research, Hartel is investigating how chimps are affected when so many of them sustain injuries from snares. This applies both to the chimps’ chances of finding food, their ability to climb trees and move around, and how it affects their social life and hierarchy within the group.

Information is the way forward

At the same time, Hartel hopes to help stop the extensive injuries caused by the snares, through the Kibale Snare Removal Programme.

“Our programme has hired six rangers who patrol the area and remove snares. This has meant that we now have a safe zone in the national park where we rarely find snares,” She says.

“One outcome is that our local group of chimps get caught up in snares less frequently," says Hartel, who is also involved in information campaigns in schools around the national park, which raise awareness about the consequences of snares.

Even though the snares are removed from the forest, this is not nearly enough to stop local trappers coming back and setting new snares, she points out.

"Snares are a problem throughout eastern central Africa because they're so easy to set. Removing a poacher's snares doesn't put him off -- he will simply set a new snare because they're so cheap to make," she says.

Uganda's rural population has been using snares for centuries, and poor rural people need to put food on the table for their families. So why should they be deprived of the right to follow their tradition of setting snares?

"It's correct that they've been setting snares for centuries. But the growth of Uganda's population has increased dramatically in recent years -- the country has been in the world top ten in terms of population growth. So the problem is that it is no longer sustainable for them to go on using the forest in the same way as they always have."

"Not all the people who set snares are locals who need to feed their families," she points out. “Foreign poachers also come along to try and earn money from illegal snare-trapping and hunting."

The 'Kibale Snare Removal Programme' is part of the Kibale Chimpanzee Project, which has now been doing research into the chimps of the Kibale National Park for almost three decades. The projects co-operate with several local organisations, including the Uganda Wildlife Authority.

--------------

Read the Danish version of this article on Videnskab.dk

Translated by: Hugh Matthews

Scientific links

- Project website: 'Effects of long-term primatological research and conservation in African forests'

- 'The Young Apes Conference website