Can birth control pills make teens depressed?

A Swedish study shows that hormone-based contraceptives are associated with an increased use of antidepressants among young girls.

Many teenagers and young adults report that they become depressed when they start using birth control pills.

But the idea that birth control pills and other contraceptives containing hormones can lead to poor mental health and depression has been controversial.

“Researchers have failed to demonstrate a connection thus far,” says PhD candidate and gender researcher Sofia Zettermark at the University of Lund to a Swedish website entitled “Vetenskap & hälsa” (Science and health).

Strong association in teenagers

To determine if there is in fact such a relationship, Zettermark compared the use of various prescription drugs in Swedish teens and women.

She found that teenaged girls who used birth control pills or other hormonal contraceptives were more likely to use sleep medications and antidepressants than others.

In the youngest girls, there was a strong link between the use of hormone contraception and the use of medicines for mental disorders, such as anxiety, restlessness, drowsiness, sleep disorders and depression.

Only four of a hundred

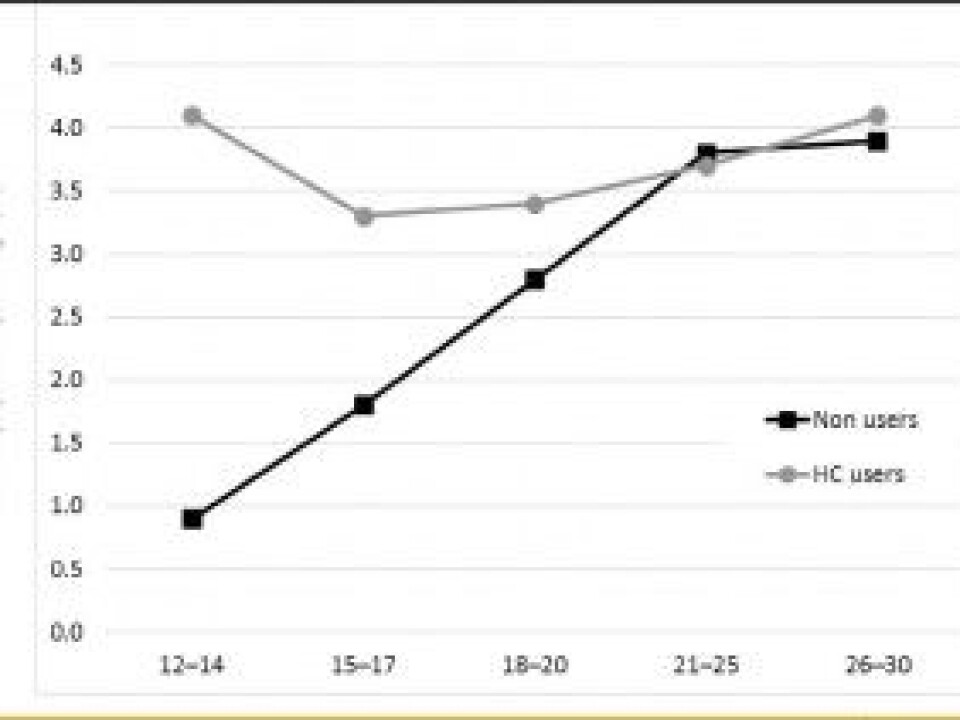

Among 12-14 year olds, just over 4 per cent of those who used hormone-based contraception used psychotropic prescription drugs.

This may sound like a small percentage, but Zettermark found that just 1 per cent of the girls who did not use hormone-base contraception used these kinds of medicines.

A 2016 study from Norway showed that the use of antidepressants among teenagers has risen sharply in the past ten years, especially among girls.

Zettermark and her colleagues found that this relationship becomes weaker as girls mature, however.

The researchers found no connection whatsoever between hormonal birth control use and psychotropic drug use in 20-year-old women.

In this group, 3.7 per cent used drugs for mental disorders, regardless of whether they used hormonal contraception or not.

The comprehensive study, which was published in PLOS ONE, comprised 800,000 Swedish girls and women between the ages of 12 and 30.

Pills not bad

The study also showed differences between different types of hormonal contraceptives.

The use of prescription drugs for mental problems was greatest among girls who used non-oral contraceptives containing hormones, such as a skin patch, implant, or vaginal ring.

The Swedish study largely agrees with what was found by a large Danish study from 2016.

Zettermark, who is also a doctor at Kiruna Hospital, says this is all the more reason to pay attention to the issue.

Sceptical about causality

Not everyone finds the study completely convincing, however. Steinar Madsen, Medical Director at the Norwegian Medicines Agency, says he thinks the study has some weaknesses.

He believes that the study doesn’t sufficiently rule out the possibility that the differences found could be due to random co-variation. Much like other studies that rely on population registers, it can difficult to sufficiently identify all differences between the two groups.

"The big problem is that girls who use birth control are not the same as those who do not use birth control,” he said. “The first group may have been in contact with the health care system earlier, for other issues.”

Additionally, many teens who use contraception do so because they are in a relationship, which in itself may cause stress.

"But it may also be that birth control pills interfere with the biology of teens to a greater extent than when they are older,” he said.

Teens shouldn’t be discouraged from using contraception

The type of study that Zettermark undertook, with relies on data from a register, makes it impossible to draw conclusions about the health of individuals. That means that researchers can’t make recommendations based on their work.

Zettermark also notes that many women who use hormonal contraceptives do well with the drugs, and that the study shouldn’t discourage young women from using hormonal-based contraceptives.

-------------------------------------

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no.