Brain cancer more common among highly educated

Persons with plenty of schooling run a higher risk of developing brain cancer, according to a survey of nearly three million Swedes.

Many studies have shown that people with university educations and high socio-economic positions live longer on average, mainly because they tend to lead healthier lives.

But a Swedish study of a large population has now detected one surprising exception.

Brain tumours are more common among persons with at least three years of higher education (college or university), as compared to persons with little education. This applies in particular to a certain kind of cancerous brain tumour, called a glioma. The new study was published last week in the Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health.

Unknown factors

The deputy director of the Cancer Registry of Norway, Dr Tom Børge Johannesen, finds the study intriguing:

“This is most interesting and represents new discoveries. The study can reveal unknown factors causing malignant brain tumours,” he says.

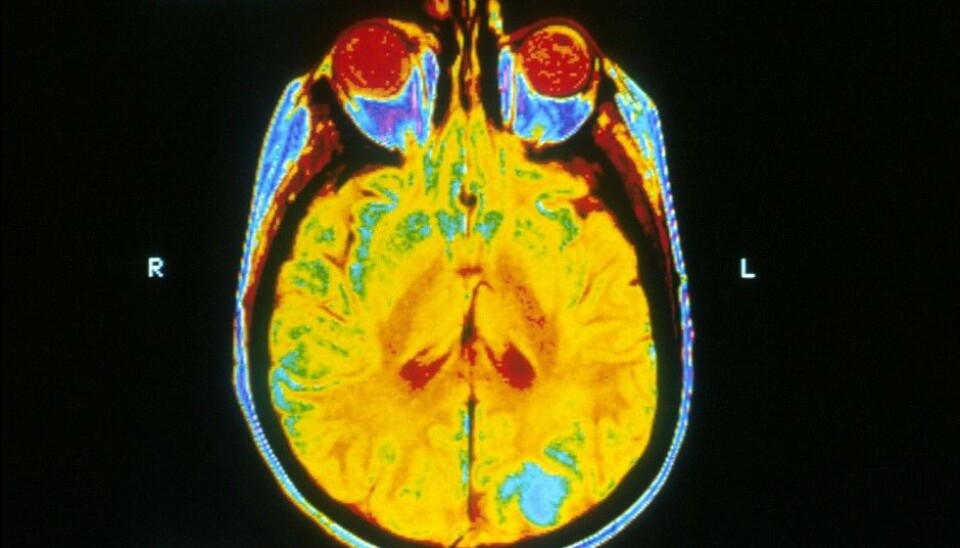

Norwegian scientists have previously found that regions in Norway that tend to use more magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of patients also see a higher incidence of brain tumours. But these are benign tumours and are often discovered by chance.

“In this study they have found an increased incidence of malignant tumours and see a possible correlation with higher levels of education. This is new,” he says.

Known causes

What is known so far about the cause of brain tumours?

“Definite causes are still high-energy radiation, in other words radioactivity, x-rays and radiotherapy, and certain genetic syndromes,” says Johannesen.

He adds that other causes such as professions, diet, mobile phone use and various lifestyles have not given any definite findings.

Another study recently showed that that the financial meltdown and credit crunch that led to recession ten years ago caused an extra half million cases of cancer worldwide.

Followed for 17 years

The researchers had data covering 4.3 million Swedes who were born from 1911 to 1961 and were living in Sweden in 1991. These persons are now aged 55 and up.

The researchers followed their health situations from 1993 to 2010 to see who developed brain cancer. Information about the extent of their education, incomes, marital status and professions was gleaned from national registers.

In the course of this period, 5,735 men and 7,100 women developed brain tumours. During these 17 years, 1.1 million Swedes died and 48,000 moved abroad.

20 percent higher risk

Men with at least three years of university-level education ran a 19 percent higher risk of developing a menacing form of cancer – a glioma – than men who quit school after ninth grade.

“Gliomas are the malignant brain cancers that start in the supporting tissue of the neurons in the brain – in the glial cells,” explains Johannesen.

The risk was even higher among women.

Highly educated women ran a 23 prosent greater risk of the same type of cancer than women without as much schooling. They also had a 16 percent higher risk of another type of brain tumour, which is usually benign.

High incomes too

The researchers controlled against other factors which could also have an impact, such as income levels and whether the persons were married or single. The latter had little effect one way or another on both sexes.

A high disposable income was linked to a 14 percent greater risk of gliomas among men but it did not have an impact on the risk of non-cancerous brain tumours.

Income levels did not impact women’s risk of contraction either benign or malignant brain tumours.

Another recent study showed that lung cancer patients in Norway with higher incomes are more often operated on than those with lower incomes – despite all being covered by national health insurance.

Office workers worse off

Professions also turned out to have an effect in this respect on both men and women.

Among men, if you have a job as a boss, a professional or office worker you run a 20 percent higher risk of getting a malignant brain tumour than men who do manual labour.

Moreover, the risk of non-malignant tumours that have an effect on balance or hearing was 50 percent higher among men in office jobs than among men who do manual labour.

Among women, those who have managerial positions or are professionals such as lawyers, doctors, etc. run a 26 percent higher risk of malignant brain tumours than working class women doing manual labour.

Women with higher educations also ran 14 percent higher risk of getting non-malignant tumours.

Men protected by single life?

Single men run a much lower risk of malignant brain tumours than men who are married or live with a partner. But they run a higher risk of benign brain tumours.

For women, the researchers could not find any significant difference in this regard, whether they were married or single.

The researchers point out that this is an observational study of statistics and they are not able to draw any conclusions about the causes or effects.

They were unable to find any information about lifestyle factors which could be having an impact on these disparities in risks.

Going more quickly to doctors?

Could it be that people with higher educations are more likely to seek medical attention earlier if they feel ill and thus get diagnosed quicker?

“It could be that going to an MD earlier can be important, since some brain tumours can lie dormant for years before being discovered,” confirms Johannesen.

Are there early signs that can be felt?

“A patient might have epileptic seizures or headaches. Those who suffer forms of paralysis will in any case be checked out with an MRI of the head region. I wouldn’t think that seeing a doctor earlier has much effect as regards those with malignant brain tumours. But it could have more of an impact for the non-malignant tumours,” says Johannesen.

------------------------------------------------

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no

Translated by: Glenn Ostling