The brain assigns symbolism to inanimate objects

Areas of the brain associated with social skills and language are activated when we relate to symbolic objects, like the national flag, shows new research.

Our brains relate to symbolic objects in the same way that they relate to social beings, shows new research.

With the help of simple Lego bricks, scientists investigated what happens in the brain when adults are exposed to symbolic objects such as the national flag or sculptures.

“It’s really interesting that the areas of the brain associated with social interaction were active when people looked at static, inanimate objects,” says lead-author Kristian Tylén, from the Interacting Minds Centre, Aarhus University, Denmark.

Tylén’s results suggest that these objects assume a symbolic meaning through social interaction.

“Numerous studies have shown differences in brain activity when we look at humans or inanimate objects. The special thing in our study is that we can see that a class of objects, what we call symbolic objects, activates the regions of the brain normally associated with social cognition and language,” he says.

The new results are published in the scientific journal NeuroImage.

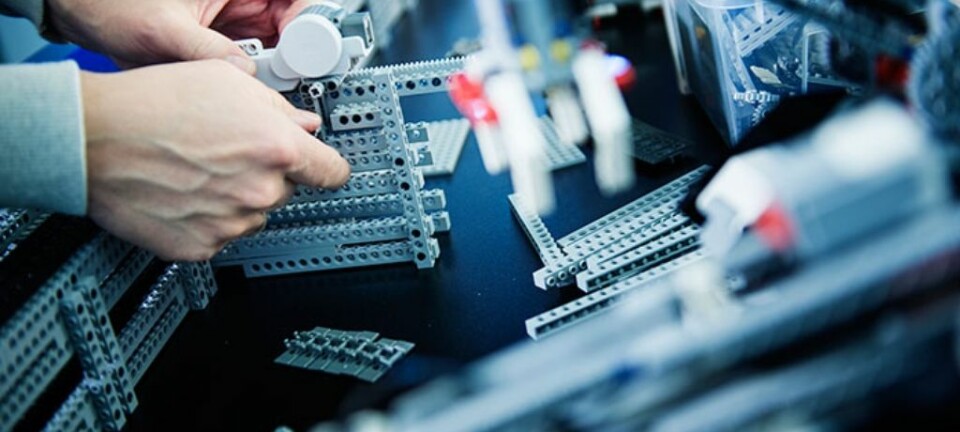

Adults play with Lego for science

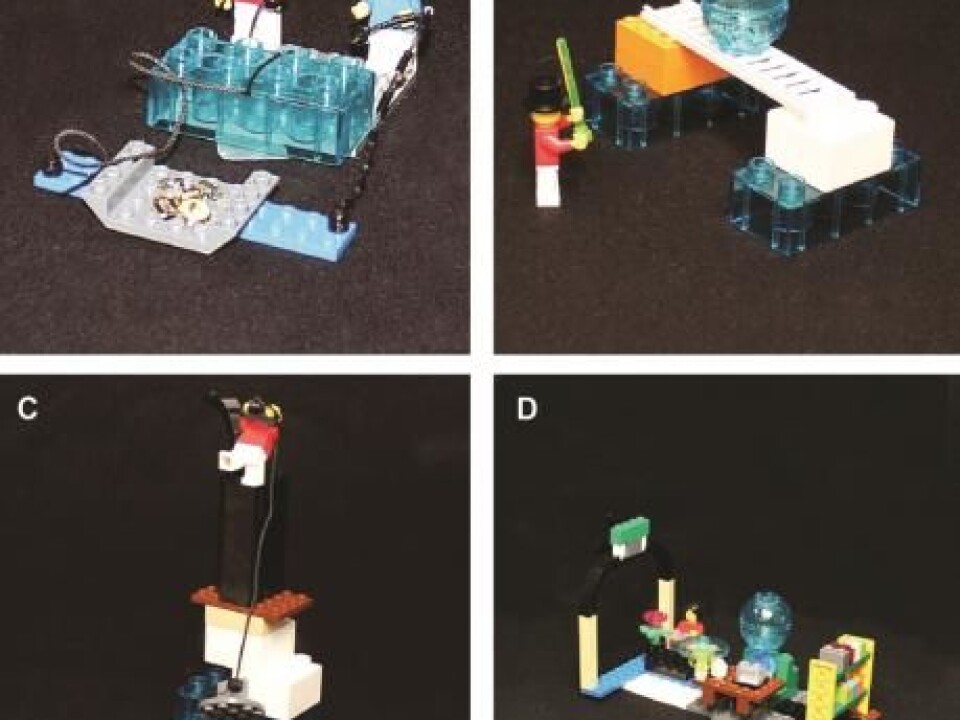

To study people’s views of symbolic objects, the scientists asked 25 study participants to build Lego models, both on their own and in groups of five. The models should illustrate the participants understanding of six abstract concepts: responsibility, cooperation, knowledge, justice, security, and tolerance.

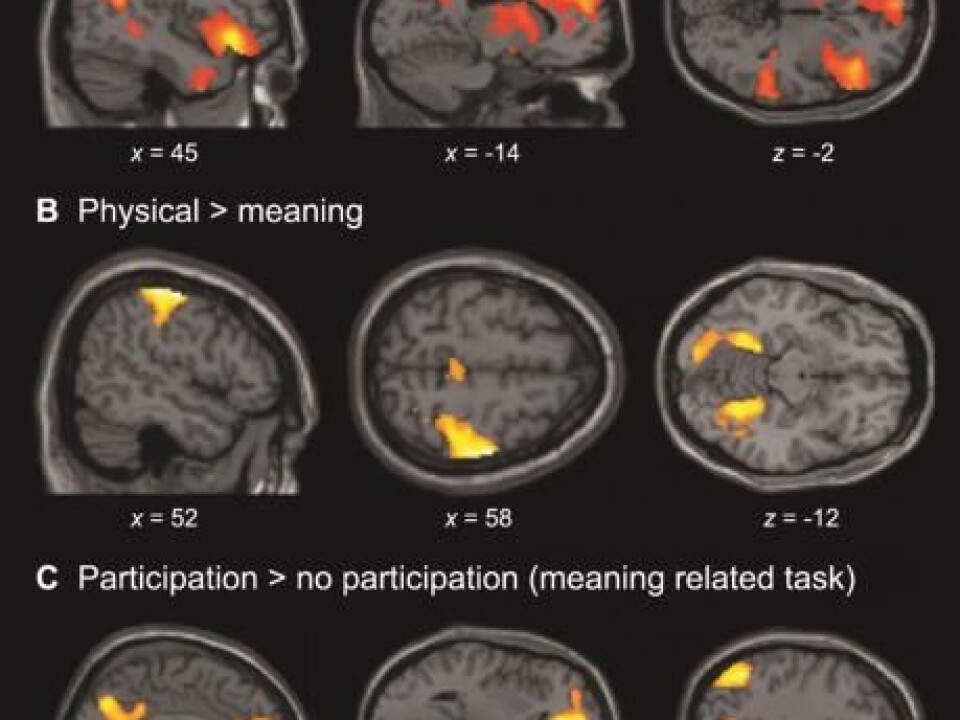

The next day each of the participants arrived individually at the laboratory and completed an fMRI brain scan while looking at the pictures of the Lego-models that they had built themselves, in groups, and models built by others.

During the scan and while looking at the Lego pictures, they were asked to describe how well the models captured each of the concepts and how durable the model was.

Read More: Using Lego to learn about machines

Social area of the brain activated

When the participants looked at the models they had helped to make, there was an increase in brain activity in the two regions associated with social cognition and language:

One region is approximately in the middle of the forehead in an area known as medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC), the other sits above and slightly behind the ears and is called the temporal-parietal hub (TPJ).

“Both of these areas are considered central in relation to our social cognition. It’s these areas that are typically activated when we imagine what other people think, feel, believe, or want. The regions are also often active if we see other people do something based on social goals,” says Tylén.

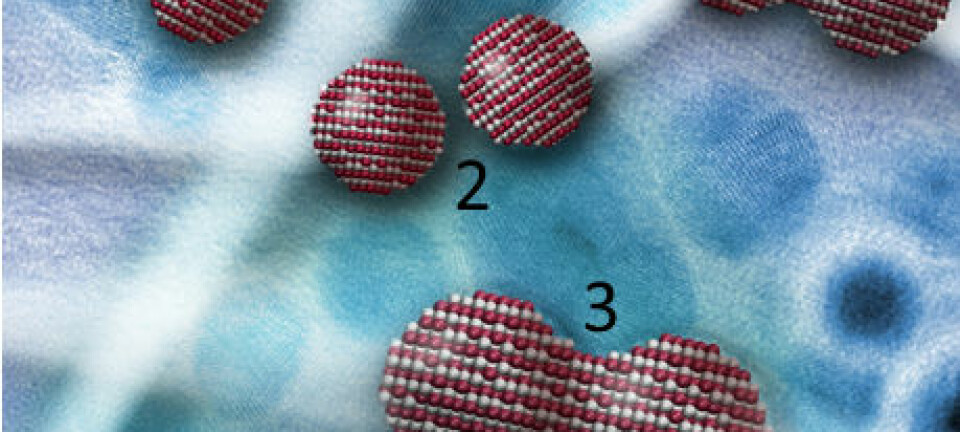

Lego models as symbolic objects

Symbolic objects have an embedded meaning that is often closely associated with the role they play in a specific social and cultural context and often only understood by people who share the same cultural background.

But how does that correlate with the Lego models?

“The models have many of the same characteristics as the symbolic objects that we surround ourselves with. On one hand they are inanimate physical things, but on the other hand they represent complex meanings that originate in the social processes, from which they emerge and are founded,” says Tylén.

Working together to build models, led to many long discussions among the participants.

“The finished Lego-models often contained complex explanations, and selections of components, colours, shapes, and so on, made by the group. But only some people from outside the group would be able to guess what the model means,” he says.

Read more: Social intelligence: The brain mirrors behaviour of others

Lego models spark empathy among participants

When participants looked at the models they themselves had helped to build, the scientists could detect increased activity in the insular cortex, which is normally associated with empathy. Brain activity in this region was even more pronounced when a participant had particularly positive feelings towards their fellow group members.

“The experiences that had been part of the previous social Lego-building process had an impact on what happens in the participants' brains when they later look at the static, physical Lego models,” says Tylén.

Colleague: Interesting implications

Associate Professor Anders Hougaard from the Department of Language and Communication at the University of Southern Denmark is excited about the study.

“An important point of the study for me is that it breaks down the established, ontological, predefined categories of objects, where for example an inanimate object is, and will be regarded as dead,” says Hougaard, and adds that the study uses a very specific set-up, but he can see many possibilities for further experiments.

“If a Lego-model can be made to arouse social cognition and emotion, then what can else be achieved with objects that integrate language, interaction online via writing, images such as selfies, and more?”

---------------------

Read the Danish version of this article on Videnskab.dk

Translated by: Catherine Jex