The biggest status symbol in the Nordic Iron Age was a goose

Poultry was all you needed to signal your status.

Forget about Gucci bags, gold jewellery, and fast cars. In the Nordic Roman Iron Age, the best status symbol was a goose. Alternatively a hen.

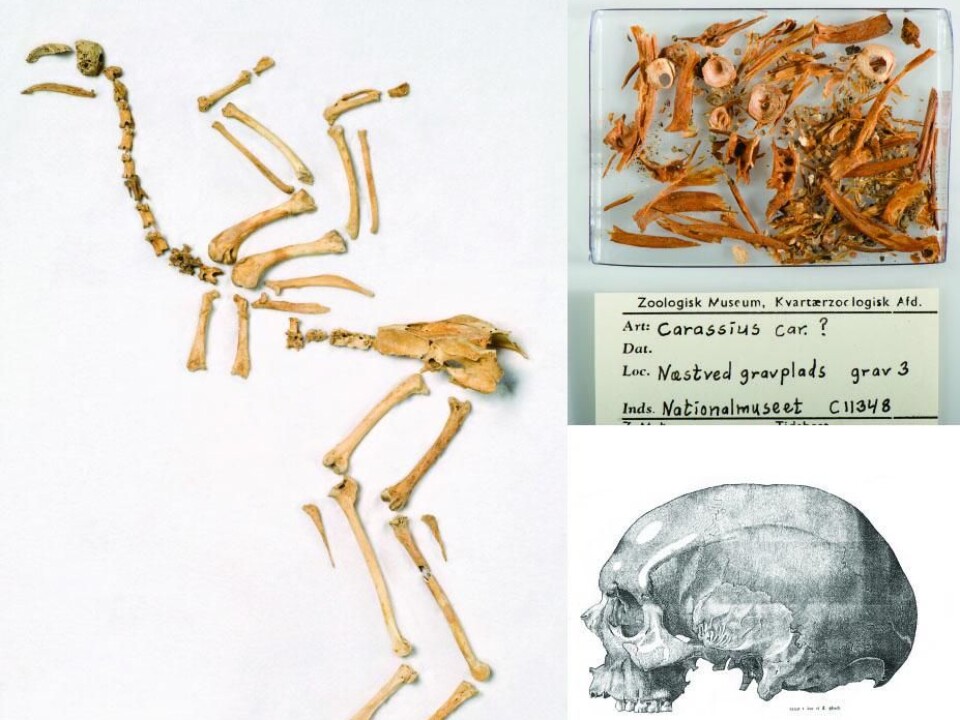

That is the conclusion made by Danish scientists after studying almost 100 graves from the Early and Late Roman Iron Age (1-375 CE).

They further posit that the Roman influence led to a significant shift in the way in which Scandinavians buried their dead.

One of the changes was the custom of burying people with different species of animals – and the newly introduced hens and geese were especially high-ranking status symbols.

“We don’t have these kinds of poultry before Christ, so it is clearly associated with the Roman life and Roman status. In the Roman Empire, hens and geese were a common burial gift, while in Denmark they were new and exotic species,” says Anne Birgitte Gotfredsen from the Natural History Museum of Denmark at the University of Copenhagen.

Gotfredsen analysed the animal bones and is lead-author on a book - Wealth and Prestige 2 - detailing the new analyses.

Read More: Archaeologists excavate 400 Iron Age houses in Denmark

More species indicates higher status

Only a select few were buried with hens or geese, and even within these two high-status symbols, there were many differences. While 'chicken graves' contained considerable valuables, it was only the 'goose graves' that contained expensive, imported Roman goods, says Anne Birgitte Gotfredsen.

“These birds were certainly rare and at this time we don’t find them in ordinary domestic waste. We only see them as whole animals in connection with rituals or in a grave,” says Gotfredsen.

The Roman influence was strong in this period and the inspiration is clearly seen in the development of burial rituals, she says. The most significant shift occurred in the transition from the Early to Late Roman Iron Age, around 150 CE.

“The number of species increases as do the number of whole animals and partial animals. The high status graves contained significantly more: More species meant higher status. There’s is no doubt that the material expression changed according to Roman inspiration,” she says.

Read More: Burnt down Iron Age house discovered in Denmark

First study of its kind

It is the first time that scientists have combined zoological studies of animal skeletons with archaeological and anthropological results in Danish graves from the Roman Iron Age period, when Scandinavia was undergoing great cultural change.

“It’s the first study of it’s kind, where material is worked on collectively and for me, it opens up entirely new aspects of burial rituals in this period,” says archaeologist Mogens Bo Henriksen, curator at Odense City Museums, Denmark.

Previously, inspiration was taken from the Roman Empire in the form of imported goods, weapons, glass beakers, bronze vessels, and coins, but the burial rituals show that the influence was much more widespread.

“The new burial rites are a clear sign of contact with the Romans, and the adoption of their animals. There are even some signs indicating that, just like the Romans, people began to hold banquets for the dead. It was an entire lifestyle,” says Henriksen.

Read More: The Viking Age should be called the Steel Age

Animals carried great symbolism

The new study allows archaeologists to learn more about the significance of the widespread practice of laying animals in graves alongside the dead, he says.

“We previously thought that the animals were buried first and foremost as food and that the grave was a locked room for the dead, but this is far from that. The animals were much more than practical and functional, they held great symbolism,” says Henriksen.

Geese, which start turning up in graves during this period, were considered holy in Roman culture. They represented the goddess Juno, who was married with Jupiter and had the highest rank in Roman mythology.

“Altogether, it sends a signal. The burials in this period were more than anything else a stage-managed event, which intended to signal lineage and thereby the status of the descendants,” he says.

Read More: Norwegian iron helped build Iron-Age Europe

Shared animals with the dead

During the transition from Early to Late Roman Iron Age, there was a change in the way in which people arranged animals inside the graves, says Gotfredsen.

For example, the practice of placing half of the animal in each end of the grave ended. Instead, they began to lay the entire animal, though still cut, in one position in the grave and the meat was cut from the bones. They also preferred to use young animals.

Gotfredsen agrees that Scandinavians acquired the Roman tradition of holding banquets around their dead, which may be supported by the new way in which people treated animals.

“We can see from the cut marks on the bones that some of the meat is cut away. This could have happened very close to the grave, which we cannot see today, but we think that the cut meat was prepared and ‘shared’ with the dead before they closed the grave,” she says.

Read More: Why some Iron Age women chose exotic jewellery

Iron Age prince surrounded by animals

One of the richest graves in the collection is the Ellekilde grave, which is dated to the Late Roman Iron Age.

In the grave, an Iron Age prince was buried with so many different species that archaeologists are in no doubt of his social status: a goose, a dog, a pig, cattle and sheep. The significance of the dog was particularly ambiguous, says Gotfredsen.

“Most animals were thought as food gifts, even though they could also have had a symbolic significance, but dogs were something else. There are no cut marks of the bones. They were a friend,” she says.

Dogs appear in many contexts in archaeological material in relation to burials and probably also had a cosmological significance, perhaps as a friend in the afterlife.

“So it certainly signalled status. We only see dogs in high status burials,” says Gotfredsen.

Dogs are also used to symbolize hunting and warfare, says Henriksen.

The Prince from Ellekilde was buried with a weapon. He is interpreted to be a warrior and his dog is thought to be a fighting dog.

--------------

Read more in the Danish article at Videnskab.dk

Translated by: Catherine Jex