Bacteria thrive at the bottom of the Mariana Trench

Scientists have found bacteria in one of the world’s most hostile and extreme environments 11 km below sea level.

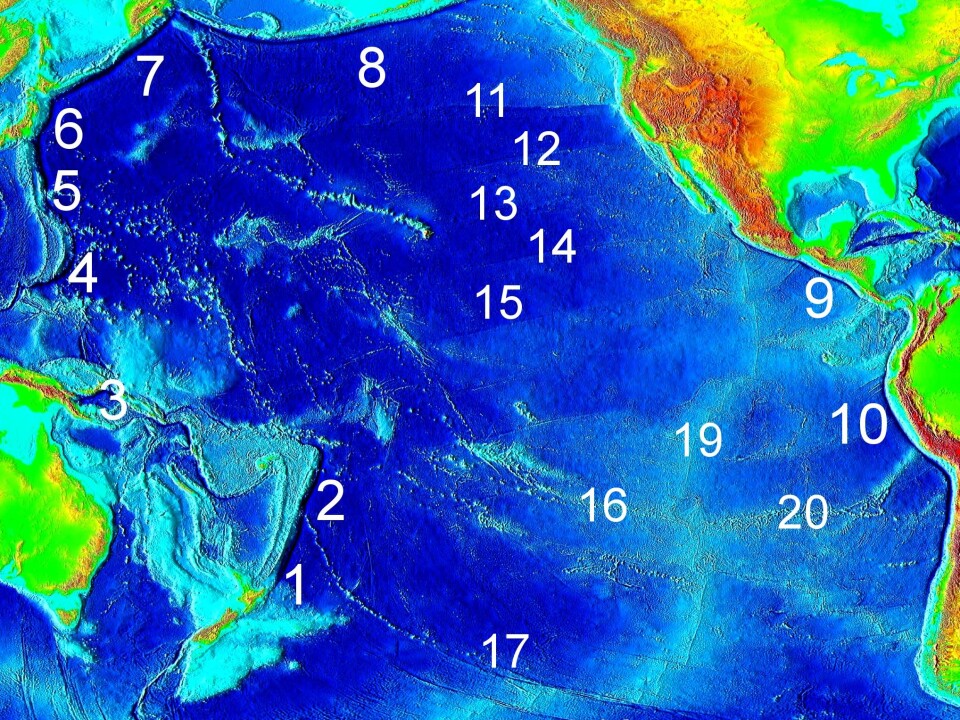

An international Danish-led research team has been examining the bottom of the deepest part of the world’s oceans, the Mariana Trench.

Their aim was to determine whether bacterial communities can function effectively under the massive pressure.

The surprising discovery was that not only can the bacteria survive the pressure at depths of 11 kilometres, they are having a great time down there, in spite of living in an extremely inhospitable environment.

”The Mariana Trench and other deep parts of the world’s oceans are ’hotspots’ for bacterial activity in the deep sea,” says Professor Ronnie Glud, of the University of Southern Denmark’s Institute of Biology, who headed the new study.

”There is a lot more activity there than one would expect – and far more than in the immediate surroundings. The reason is that the trenches contain plenty of food for the bacteria to feed on. Our discovery presents an important step towards an understanding of what happens to all the organic matter from dead fish and algae when it falls to the seabed.”

Discovery clarifies previous assumptions

Scientists would normally say that the deeper down the sea floor is, the fewer bacteria are to be found.

The seabed in coastal areas, where food supplies are plentiful, is teeming with bacteria. As the water becomes deeper, the food source for the bacteria starts to disappear.

The new discovery adds some nuances to this conception:

The Mariana Trench and other deep parts of the world’s oceans are ’hotspots’ for bacterial activity in the deep sea.

“Fifty percent of the seabed lies in what we call the abyssal plain, which is found at depths between 4,000 and 6,000 metres. Here, there is not much bacterial activity. But where the sea is even deeper, as in the major oceanic trenches, the bacterial activity increases again,” says Glud.

Danish researchers have also recently found that bacteria thrive deep below the seabed in the rocks that make up the earth’s crust.

What happens to the organic matter?

The apparent fact that bacteria can thrive at such extreme depths can be attributed to their food, which comes in the shape of organic matter.

Scientists have long been assuming that the great trenches such as the Mariana Trench, the Japan Trench and the Philippine Trench act as funnels through which large amounts of organic matter disappear.

Our discovery presents an important step towards an understanding of what happens to all the organic matter from dead fish and algae when it falls to the seabed.

The big question has been: what happens to all this organic matter?

”Our main objective is to understand the global carbon cycle and how much CO2 the ocean fixes. This ultimately determines how much oxygen there is on Earth. When algae absorb CO2 and later sink to the bottom, it is important to understand what happens to the algae,” says the researcher.

“Do they turn into oil, or are they converted by bacteria which reintroduce CO2 into the carbon cycle? Our findings from the Mariana Trench show that there are bacteria that feed on the dead algae and all the other organic matter that sinks down into the deep trenches and thus keep the carbon cycle running.”

Only extreme bacteria can survive down there

It takes a pretty special bacterium to survive the harsh conditions 11 kilometres below sea level:

Our findings from the Mariana Trench show that there are bacteria that feed on the dead algae and all the other organic matter that sinks down into the deep trenches and thus keep the carbon cycle running.

”These are unique, specially adapted bacteria that live at the bottom of the Mariana Trench. We have now started a project that aims to uncover how the bacteria can survive under this enormous pressure. This must require some very special cell membranes and enzymes.”

Moreover, the bacteria do not survive only on a minimum of activity at the bottom of the trenches. The new findings show that they are extremely active in their conversion of the organic matter that sinks down from above.

Measuring instrument in free fall

Lowering the measuring equipment down 10,900 metres was in itself a great achievement for the researchers, who had to construct specially-designed gauges that could deal with the intense pressure below.

After a three-hour long free fall, the measuring instrument hit the bottom, where it measured the oxygen contents as an indication of bacterial activity.

The oxygen content in the sediment is a very good indicator of bacterial activity, since the bacteria use oxygen to convert the organic matter. This means that the less oxygen there is in the sediment, the more active the bacteria.

“In the parts of the sea where there is virtually no fallout of organic matter, the oxygen can penetrate 50 metres down into the seabed. At the bottom of the Mariana Trench, the oxygen ‘only’ penetrates one metre down, which suggests that there is a relatively high bacterial activity,” says Glud.

-------------------------

Read the Danish version of this article at videnskab.dk

Translated by: Dann Vinther