Arthritic kids feel pain even after successful treatment

Some children with arthritis experience pain on a daily basis even after successful treatment of the disease. Why is it that the pain doesn’t always go away when the disease does?

Do kids feel pain?

Up the 1980s, our view of children’s pain and how it should be treated was a lot different than it is today.

An infant’s experience of pain was considered to be minimal due to an immature neurological system. This meant that painful surgery processes were often undergone with little or no minimal use of anaesthetics.

Such was also the case with arthritic children. It was believed that they felt less pain than adults with arthritis. The result was that the children received inadequate treatment for their disease.

Today we know that children experience the same levels of pain as adults do, and this is also reflected in improved treatment, where anaesthetics have become an integral part in operations of children.

Being an arthritic child is painful

The treatment of arthritis has seen great improvements in the past 15 years in line with the development of new forms of medical treatment.

Juvenile idiopathic arthritis is one of the most common chronic diseases that start in childhood.

The arthritis is caused by joint inflammation, and thanks to the improved treatment options, most of today’s arthritic children experience great reductions in inflammation, and these inflammations can usually be kept at bay with treatment.

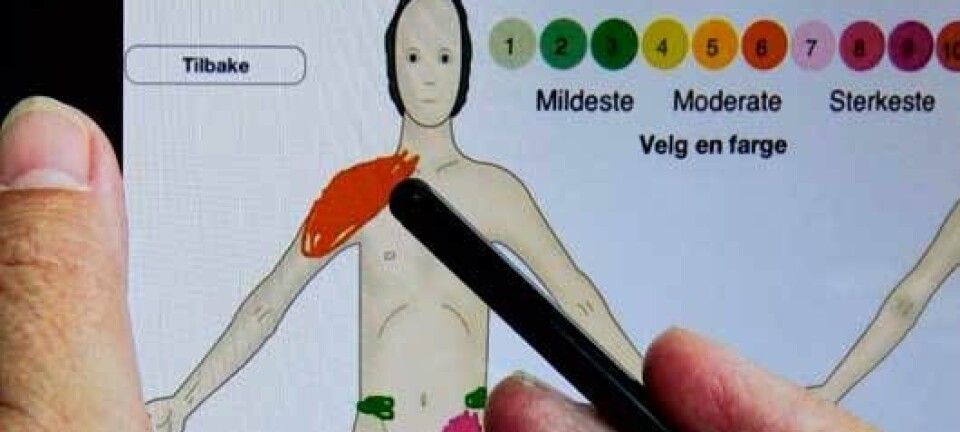

However, despite effective treatment of the arthritis, we found in a study that almost one in three children with arthritis experienced daily pains. How can we explain that?

Cracking the pain code

The medical community has traditionally regarded pains as being exclusively affected by physiological factors, such as the severity of the disease or the seriousness of an injury.

The pain could affect the individual and thus also the individual’s environment, but not the other way round: pain was an entirely physiological phenomenon. This view, which can be traced back to René Descartes in the 17th century, has been greatly challenged in the past 50 years.

This has resulted in our current understanding that other factors in the individual and in his or her surroundings play a part in relation to the pain we feel.

For example, if you get your fingers caught in the door one morning when you have overslept – and it’s raining, which may affect your mood – it would feel more painful than, all else being equal, if the same thing were to happen on a sunny day when you’re in a good mood.

Or if you twist your ankle in a football game for the fifth time this season and you know it’s a sprain, which merely requires a couple of weeks to heal, this pain will be different and will most likely be felt more severely than if it were the first time it happened and you feared that it was a serious injury.

Why doesn’t the pain disappear with the disease?

In order to explain why a third of arthritic children still experience daily pain even though the inflammation in the joins has been reduced, it is therefore necessary to look beyond the disease itself.

- One possible explanation is that children with arthritis have a significantly lower pain threshold than healthy children. It appears that it is the inflammation in the joints that affect the nerves in a way that makes it easier to transmit pain signals, which then results in a faster pain response in the child.

- Another possible explanation is that the thoughts that children have about pain and what it can do to them has an effect on how they experience the pain. Thoughts about the pain as being a catastrophe, e.g. ‘This pain will never go away!’ and ‘I just can’t stand this pain!’ are correlated with an increase in felt pain.

There is, however, no clear-cut explanation to why the pain and the recovery from this disease do not go hand in hand. And that makes it an area in which there is room for a lot more research.

Thoughts are crucial for enduring the pain

In a group therapy setting we focused on the children’s beliefs about pain and how the children coped with their pain.

Although the children did not feel that their pains were reduced after the group therapy, they felt an increase in well-being and that it became easier for them to get through the painful days.

In other words, it is possible to improve the children’s well-being even though the pains are still present. And it is exactly this well-being that is the foundation for creating a good childhood.

--------------------------

Read the Danish version of this article at videnskab.dk

Translated by: Dann Vinther

Scientific links

- "Science is not enough: the modern history of pediatric pain", Pain (2011), DOI: 10.1016

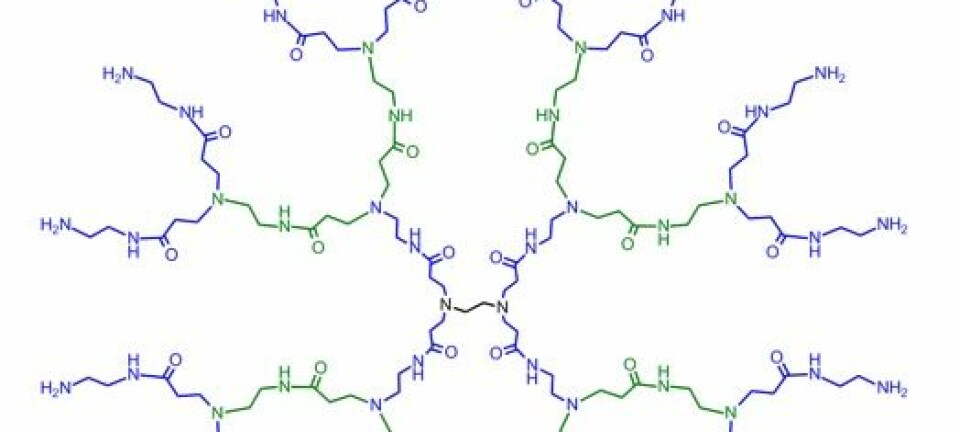

- "Pain experience in children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis treated with anti-TNF agents compared to non-biologic standard treatment", Pediatr Rheumatol Online J (2013), DOI: 10.1186

- "Decreased Pain Threshold in Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis: A Cross-sectional Study", J Rheumatol (2013)