This Arctic town has running water for just four months of the year

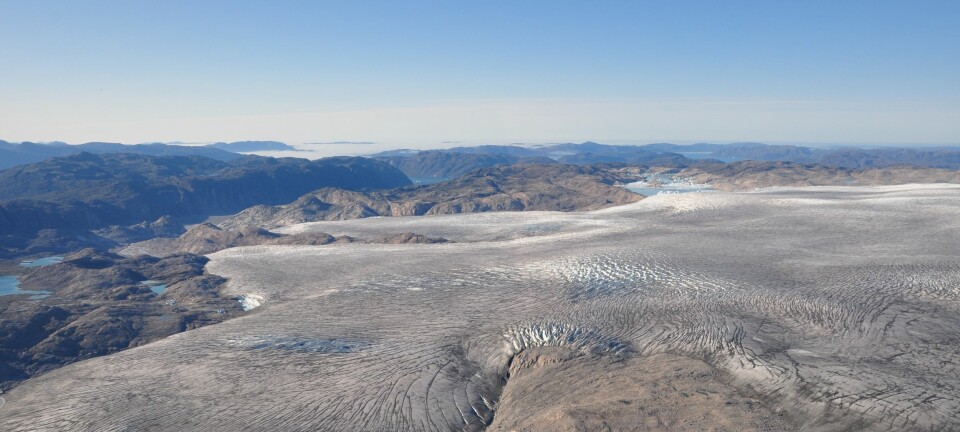

GREENLAND: How do you supply running water when it is frozen for most of the year? The Greenlandic town of Qaanaaq has some creative solutions.

Greenland has no national grid to supply electricity and water to all of its towns and villages. Residents in Qaanaaq--Greenland’s northern most town--have to be creative when it comes to providing these basic services.

Qaanaaq is so far north that for eight months of the year it is simply too cold for rivers to flow.

Here, scientists are coming up with solutions to the unique challenges faced by inhabitants in the high Arctic.

“Local inhabitants and society in Qaanaaq are up against very clear engineering challenges with regard to power, water, and waste,” says Kåre Hendriksen, from the Centre for Arctic Technology at the Technical University of Denmark (DTU).

Hendriksen has been finding solutions to many of these issues in Greenland’s remote settlements for 20 years.

Winter is a challenge

Winter in Greenland’s most northerly town brings with it a unique set of challenges.

Drinking water is frozen for much of the year and current solutions are enormously expensive and not always environmentally friendly.

Qaanaaq is a town of about 640 inhabitants, perched on a rocky slope and built on permafrost—ground that is frozen for two or more years.

For four months in the summer, residents get their water from a nearby river and fill up water tanks, which provide water for another four months.

This leaves the city with a serious challenge for the remaining four months of the year before the river starts to flow again.

Read More: Greenland in numbers: eight key statistics to understand the world’s largest island

Drinking water from icebergs

To keep the town supplied with water during the Arctic winter, dump trucks head out onto the sea ice to collect icebergs.

The trip can be dangerous. Particularly towards the end of the winter as the Arctic transitions into spring, when sea ice starts to thin and break apart from the action of currents in the water beneath.

On land, the ice is tipped into a large smelter to create drinking water that is sent out in the distribution network.

It is a costly method. Drinking water here is the most expensive in Greenland and costs consumers up to 16 times as much per cubic metre than cities in mainland Europe.

To avoid the thinning ice, stocks of icebergs are deposited on the beaches around the town, where it risks contamination from other domestic waste--including kitchen waste and sewage--that are stored on the beach in plastic bags.

More often than not, the water stores run dry just as locals’ consumption needs are highest.

Qaanaaq’s burgeoning halibut industry, part of the Arctic’s expanding fishing industry, is one such example. Fish are brought to shore, and need to be cleaned and stored at a time when water is at its most expensive. High water and electricity costs mean that the town’s largest industry is simply unprofitable.

Climate change requires new solutions in the Arctic

Climate change means that the safe period for driving out on the sea ice has become ever shorter. And as the trend looks set to continue, it is imperative that Arctic towns like Qaanaaq find a more permanent solution to their water supply worries.

There are several solutions, but none are cheap or problem free, says Hendriksen.

“One option is to see if there is running water deeper down in the river,” says Hendriksen.

“The river runs on a bed of large boulders, which means that there could be hidden pockets of water that are continuously full, even if the river on the surface appears to be dry,” he says.

Simply building more water tanks to increase capacity is another option. But even this is problematic, as they will be built on permafrost, which has its own engineering difficulties.

“We have to heat the water, so it doesn’t freeze in the harsh winter, but warming poses a threat to the permafrost on which the tanks are built. This requires good tank insulation and it’s an expensive option,” says Hendriksen.

Read More: Heavy summer rain in Greenland speeds up ice melt

Building deep lakes and desalination plants

Building deep lakes that allow for two metres of frozen water at the surface and fresh water that can be pumped out of the lake is a cheaper alternative. But again, building in permafrost makes it difficult to seal the bottom of the lake to ensure that the water doesn’t simply drain away.

A final option is to desalinate seawater. Desalination plants are already operational elsewhere in Greenland. Here in the far north however, such an operation would be extremely expensive and technically challenging.

“Around Qaanaaq, ice closest to land melts first due to the stone reef located just next to the city. This makes it very difficult to lay a pipe that can pump water in to the town,” says Hendriksen.

Offshore pipes would need to extend 500 metres off shore to avoid pumping contaminated water from domestic waste deposited on local beaches. And such a pipeline would need to be able to withstand the physical stresses and strain exerted by melting ice on land and at sea, he says.

Hendriksen continues to test solutions to keep the taps flowing in high Arctic towns like Qaanaaq.

----------------

Read the Danish version of this story on Videnskab.dk

Translated by: Catherine Jex