Anus-mouthed worm looks like our earliest ancestor

Scientists have finally succeeded in studying the development of a tiny Swedish worm. Its mouth and its anus are in the same spot and the worm is a primitive form of man.

You have a family member with no anus, but it has the potential for serious verbal diarrhea.

If it’s of any reassurance, let’s make it clear that we’re talking about a 2-3 cm long worm with a flat body, which looks like our 600 million-year-old original form.

The worm goes by the name of Xenoturbella bocki, which, roughly translated, means ‘Bock’s strange tubellarian’.

Despite its tiny size, the Xenoturbella bocki has been the cause of heated debate among the world’s evolutionary scientists.

We’re talking about our own origins because we come from the same ancestor. And since the Xenoturbella hasn’t changed much over all these years, it still looks like the distant progenitor of us humans and a host of other animals living today.

For decades, researchers from several countries have been collecting and studying specimens, and in numerous scientific articles they have developed, contributed to or dismissed theories of where on life’s genealogical tree the Xenoturbella belongs.

Now an international research team has made a long-awaited scientific breakthrough regarding the tiny worm.

Researchers kept worm alive

For the first time ever, scientists have managed to study embryos and newly-hatched offspring from the Xenoturbella bock.

“They can be found by taking hundreds of kilos of mud up from the seabed and then waiting for them to crawl out of the mud. But they are so difficult to keep alive that no-one has succeeded in doing this until now. The Japanese marine biologist Hiroaki Nakano, of Gothenburg University, Sweden, has not only managed to keep them alive – they have even reproduced,” biologist Peter Funch of Aarhus University told the university’s scientific newsletter RØMER.

You can learn a lot about evolution by studying the embryonic development. In the earliest stages of a human embryo, we can for instance see gills as a relic from earlier evolutionary stages.

“We’re talking about our own origins because we come from the same ancestor. And since the Xenoturbella hasn’t changed much over all these years, it still looks like the distant progenitor of us humans and a host of other animals living today.”

This means that the researchers have now put a face on an ancestor, even though it neither has eyes nor a brain – only a hint of a mouth, and the newly-hatched worms have yet to develop an anus.

Researchers studied worm embryos

It was previously believed that the Xenoturbella had evolved ‘backwards’ over the years from a more advanced original form.

But the new study indicates otherwise, showing that the worm is a direct developer without a larval stage. This has made the researchers more confident about the worm’s placement on the genealogical tree.

“You can learn a lot about evolution by studying the embryonic development. In the earliest stages of a human embryo, we can for instance see gills as a relic from earlier evolutionary stages,” says Funch.

“It’s also an important tool in research like this. Even though DNA technology is an effective tool for analysing kinship, it’s still subject to uncertainty when it comes to evolution, which has occurred quickly and millions of years ago.”

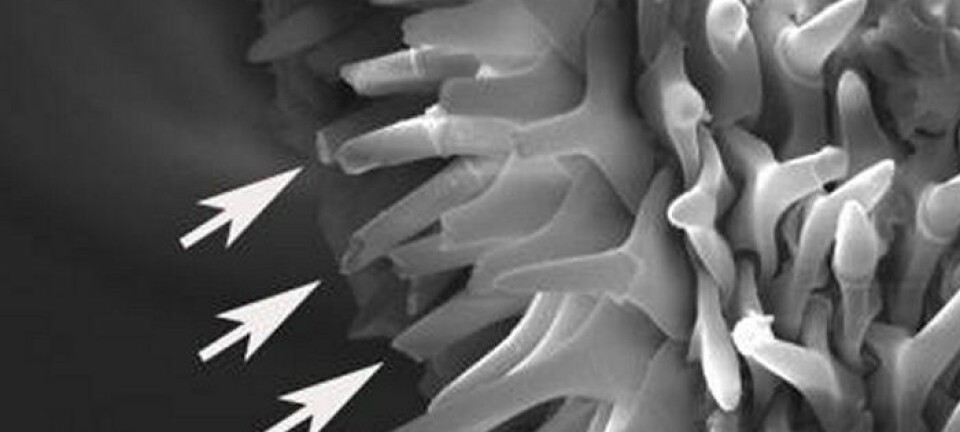

Mouth functions as an anus

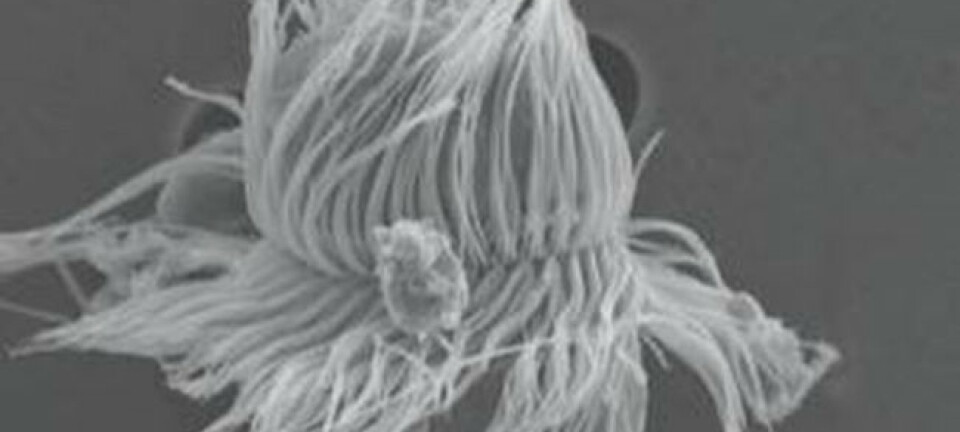

The Xenoturbella’s flat body is slightly tapered at both ends and covered by cilia, which it uses to move around on the seabed off the coasts of Sweden, Iceland and Scotland.

It eats its food through an opening in the middle of the belly, digests the food in the bowels and sends the faeces out again though the same opening from which it came. In other words, the mouth also acts as an anus.

The worm has no brain, no kidneys, no actual sexual organs, and its nervous system is extremely primitive.

The Xenoturbella was studied by the Swedish zoologist Sixten Bock in 1915, but it wasn’t until 1949 that it became described as a species.

Today, ’Bock’s strange tubellarian’ has its very own chapter in biologists’ textbooks.

--------------------------

Read the Danish version of this article at videnskab.dk

Translated by: Dann Vinther