Antioxidants doubled spread of cancer in mice and human cells

Scientific opinion on antioxidants shifts, as the ‘anticancer’ wonder turns out to be doing more harm than good.

Antioxidants found in dietary supplements and skin lotions, such as vitamin E and beta-carotene, are often marketed for their anticancer benefits because they attack cancer-causing free radicals in the body.

This has led many medical professionals and nutrition experts to believe that supplements rich in these antioxidants will protect us from developing cancer--and perhaps even help cancer patients to defeat the disease.

But this mantra, despite its popularity, is based on very little direct evidence and a very troublesome picture is slowly emerging. Antioxidant supplements may not only have no anticancer benefits, they may even cause some forms of cancer to become more aggressive.

New research published in the scientific journal Science Transitional Medicine is the latest in a series of studies to suggest that any excessive intake of antioxidant supplements could be dangerous.

“High levels of antioxidants increase the invasive behaviour of skin cancer cells, allowing the cancer to spread more effectively to other tissue,” says co-author Professor Martin Bergö, from the Sahlgrenska Cancer Center at the University of Gothenburg, Sweden.

“Patients diagnosed with cancer should not take antioxidant supplements as a way to protect themselves, because the chance that they will worsen the cancer is quite large,” says Bergö.

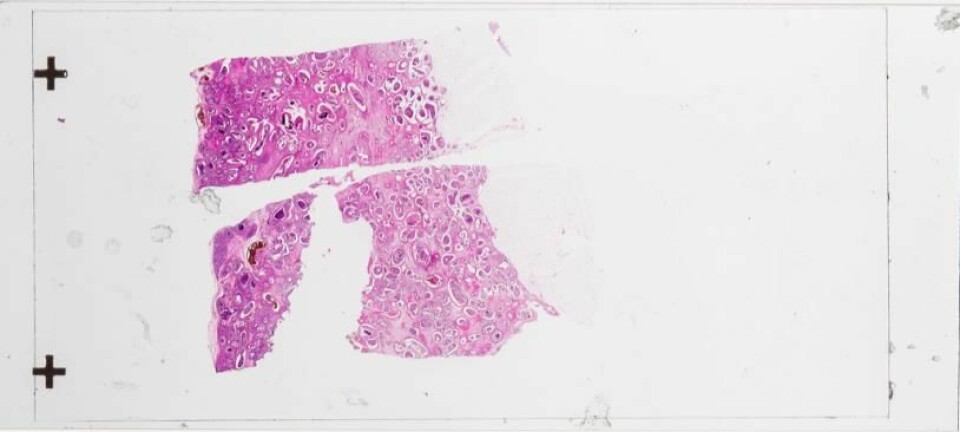

In the new study, mice and human cells with skin cancer were exposed to antioxidants, and shortly after the cancer cells started spreading at double the rate.

A change in scientific opinion

All kinds of studies have attempted to investigate antioxidants’ supposed anti-carcinogenic effect but they have found little concrete evidence--which could be why there is such a confusion among health professionals today, says Bergö.

“If you look at the studies, the overall results are inconclusive,” he says. A statement echoed by epidemiologist and cancer researcher Michael Goodman from the Rollins School of Public Health, Emory University, USA, who was lead-author on a review of the role of antioxidants in cancer prevention in 2011.

“There’s no credible evidence that antioxidant supplementation positively affects health in general, or cancer risk in particular,” says Goodman.

The two researchers are not alone in this conclusion.

Two of the largest clinical trials, which set out to test the role of antioxidants in cancer prevention, had to be aborted early when the patients who received antioxidants started to develop cancer at significantly higher rates than the control groups.

“Even though these studies indicated that antioxidant [supplements] might be dangerous, they were pretty much ignored,” says Bergö.

Antioxidants made lung cancer worse

In a study from 2014, Bergö and colleagues picked up where the previous research had left off and tested specifically how lung tumours in mice would react to the two antioxidants N-acetylcysteine (NAC) and vitamin E.

The results were troubling. When the tumours were exposed to either of the two antioxidants, they grew bigger and increased in number when compared to a control group.

It was the first time that scientists could prove a direct link between antioxidants and a negative effect on cancer development.

NAC and vitamin E are common antioxidants used in food supplements and vitamin E is also added to many skin creams and sun lotions.

Bergö’s research suggested that in high quantities they made existing lung tumours more aggressive.

Skin cancer became virulent when exposed to antioxidants

In the new study, Bergö and his team turned their attention towards skin cancer, which is rapidly increasing in both incidence and lethality around the world.

What’s more, skin cancers could be frequently exposed to an excess of antioxidants such as vitamin E, via the direct application of sunscreens and skin lotions.

Again, the results were troubling.

When mice and human cells with skin cancer were exposed to high doses of NAC and vitamin E, the cancer started spreading at double the rate, when compared to a control group

“This is really alarming because metastasis is what kills cancer patients--and not the primary tumour as that is usually operated away, especially on the skin,” says Bergö.

Goodman calls the study yet another in a growing line of evidence that antioxidant supplements can be harmful.

“It is likely that foods rich in antioxidants--but not supplements--are beneficial,” he says.

The new mantra seems to be “everything in moderation” but certainly no antioxidant supplements.

Antioxidants have become an industry

At the University of Copenhagen, the new results do not come as a shock to Lars Ove Dragsted, professor and head of section at the Department of Preventive and Clinical Nutrition.

He describes how the health effects of antioxidants are complex and in general misunderstood by many people--including health professionals.

“Labelling something as an antioxidant is like labelling a person as either good or bad--it’s too simple. Depending on the environment, a person may be good or bad, and the same is true of so-called antioxidants,” says Dragsted.

“We need to understand that in certain circumstances, like lung cancer or skin cancer, they may be bad for us, but in other circumstances they may be good,” he says.

But Dragsted has little faith that such misconceptions will change soon.

“Unfortunately, there is so much cash pumped into promoting so-called ’antioxidants’ as supplements to food and cosmetics, that this [correcting the misconception] is now virtually impossible,” he says.

Be careful with antioxidants even if you don’t have cancer

But what about healthy people? Can they take antioxidant supplements without any ill effects? Bergö is worried by this, as it can be very difficult to know for sure if someone is completely free of cancer.

A person can go any number of years with undiagnosed tumours in the lung and on the skin, says Bergö. If they are taking antioxidant supplements then it could be a serious issue.

“They could boost the progression of a tumour without knowing it,” says Bergö.

When asked whether research of this nature could lead to a paradigm shift in the medical professions’ view on antioxidants he becomes hesitant.

“I really don’t know. This dogma is so deep-rooted. I’ve had people scream at me at conferences over this,” says Bergö.

“You know there are people who make a whole career trying to make new, effective antioxidants, and there are companies who make a living selling supplements with antioxidants. The supplement industry as a whole is a multi-billion dollar enterprise, so it’s a difficult subject to raise,” he says.