Aerial photos from Greenland topple climate models

Greenland’s ice sheet is not behaving as scientists have expected, and the climate models must be revised, new research suggests.

Scientists have long believed that Greenland’s ice sheet is melting with increasing speed and that this will result in considerable rises in water levels in the world’s oceans over the next 100 years.

But the foundation for this view now appears to be completely wrong.

In the latest issue of the journal Science, Danish researchers report that Greenland’s ice sheet is not behaving quite as expected – the speed at which the ice disappears rises and falls considerably when measured over the years.

The climate models for the influence of melting ice on water levels in the oceans must therefore be revised.

Such is the message from the researchers, who are completely aware that they are touching on a controversial subject.

“Yes, this is controversial,” admits Kurt Kjær, the science director at the Natural History Museum of Denmark, which is part of the University of Copenhagen (KU).

“This is no doubt also the reason why Science is publishing it – this report brings us another step along the path to understanding the dynamics of Greenland’s ice sheet.”

Together with some of Denmark’s leading researchers at KU, the Technical University of Denmark (DTU) and Aarhus University, Kjær is responsible for the sensational results.

Greenland’s ice mass shrinks periodically

The ice mass around and on Greenland shrinks because of two effects:

- Ice melting and the amount of precipitation – these two factors give a negative net result which means Greenland’s ice mass shrinks.

- Ice that flows out to sea and calving – ice that breaks off from glaciers. This form of loss of ice mass is called ‘dynamic ice-mass loss’ and it can be many times higher than the loss of ice due to melting. An example of this form of ice-mass loss is a piece of the Peterman Glacier in northwestern Greenland, which broke off in June this year – it was twice as large as Manhattan.

Until now, researchers have believed that the dynamic ice-mass loss accelerated constantly. Most climate models are based on this belief.

But the new research indicates that the dynamic ice-mass loss fluctuates over a period of several years.

Between 1985 and 1992, Greenland experienced a large loss of ice mass because of dynamic ice-mass loss. But the glaciers stabilised and there was no dynamic ice-mass loss for more than ten years.

This loss started again in 2004 and has continued until today.

“We can see that the dynamic ice-mass loss is not accelerating constantly, as we had believed,” says Shfaqat Abbas Khan, a senior researcher at DTU Space – the National Space Institute.

“It is only periodically that the ice disappears as rapidly as is happening today. We expect that the reduction in Greenland’s ice mass due to the dynamic ice-mass loss will ease over the next couple of years and will reach zero again.”

Khan emphasises, however, that the ice-mass loss due to melting continues unabated.

Aerial photos from the 1980s a source of new knowledge

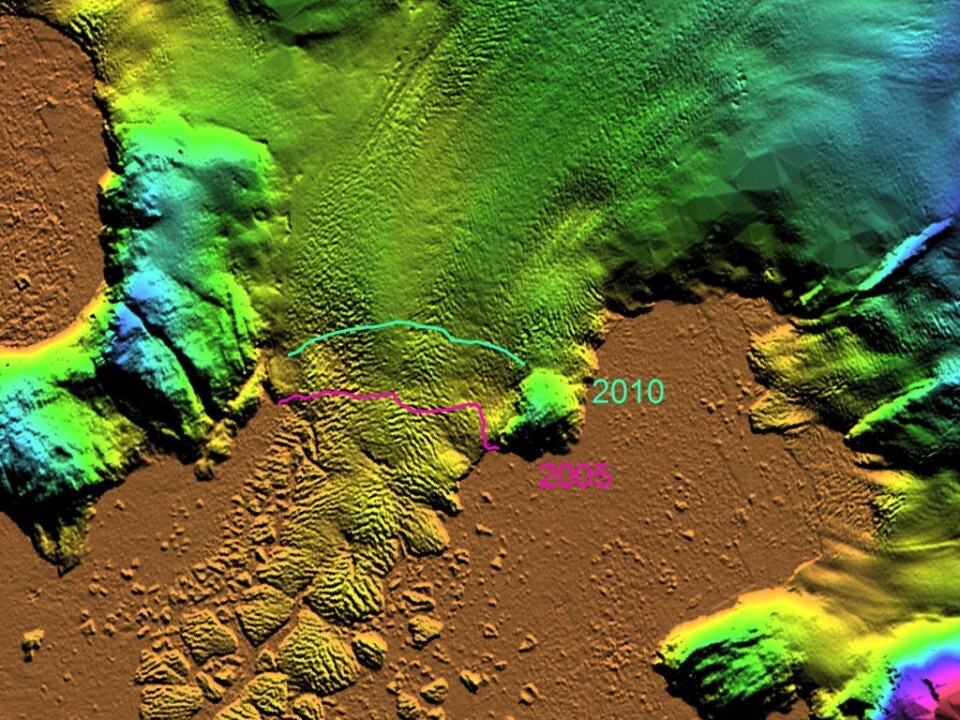

The new findings derive from photos of glaciers over a 700-km stretch of northwestern Greenland, taken 20 to 30 years ago from aircraft.

Using those pictures and newer satellite images, the researchers drew a digital physical map of the inland ice-sheet’s development, including the thickness of the ice sheet, over the past 30 years.

On this basis, the researchers’ analysis showed that the glaciers also had large dynamic ice-mass losses in the period 1985-1992 – and that the loss has since stopped.

“All existing reports about the dynamic ice-mass loss are based solely on satellite photos from the past 12 years,” says Khan. “So we didn’t know until now that the ice-mass loss also occurred earlier and perhaps takes place at regular intervals.”

“I believe that Greenland has had dynamic ice-mass losses in all previous ages,” adds Kjær. “But we don’t yet know whether global warming has intensified them.”

Climate models must be revised

The new knowledge must be incorporated into the existing climate models if these models are to give a sensible indication of how melting ice will impact on water levels in the oceans.

“The climate models must be changed to reflect our new understanding of how and why the dynamic ice-mass loss takes place as events and whether these are cyclical or their frequency changes,” says Kjær.

“If these new findings are not included in the climate models we can end up over-estimating the rises in ocean water levels,” adds Khan.

----------------------------------

Read the Danish version of this article at videnskab.dk

Translated by: Michael de Laine