3,500-year-old gemstones cast light on a forgotten civilisation

On a small island in Kuwait, archaeologists have discovered a jewellery workshop containing 3,500 year old semiprecious stones.

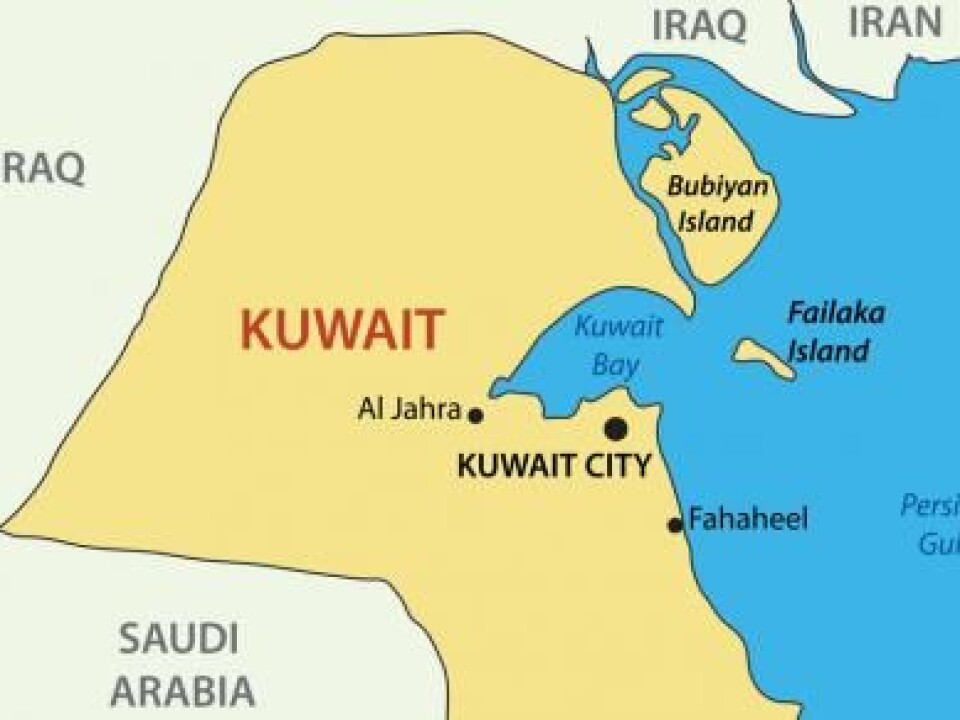

For the last nine years, the small island of Failaka, just off the Kuwaiti coast has been home to a group of Danish archaeologists from Moesgaard Museum in Aarhus, Denmark.

The archaeologists are there to investigate remains of the Dilmun Civilisation, which lived on the island in the period 2100 to 1700 BCE. Back then, Failaka was a stronghold for trade between large towns in Mesopotamia, in present day Iraq.

It was wealthy period in The Arabian Gulf, driven primarily by trade in copper from the mountains of Oman.

But this trading network completely collapsed around 1700 BCE, when temples and cities were abandoned, the King’s grave was plundered, and people tightened their belts. It became a sort of “dark ages” and very little is known about it.

Now, archaeologists have made a discovery that could shed some light over the period.

“We discovered the remains of a jewellery workshop in the settlement dating to between 1700 and 1600 BCE. Among the domestic waste we found fragments of gemstones. These stones aren’t found on the island of Failaka, but were imported—probably from India and Pakistan,” says excavation leader Flemming Højland who is an archaeologist and curator at Moesgaard Museum.

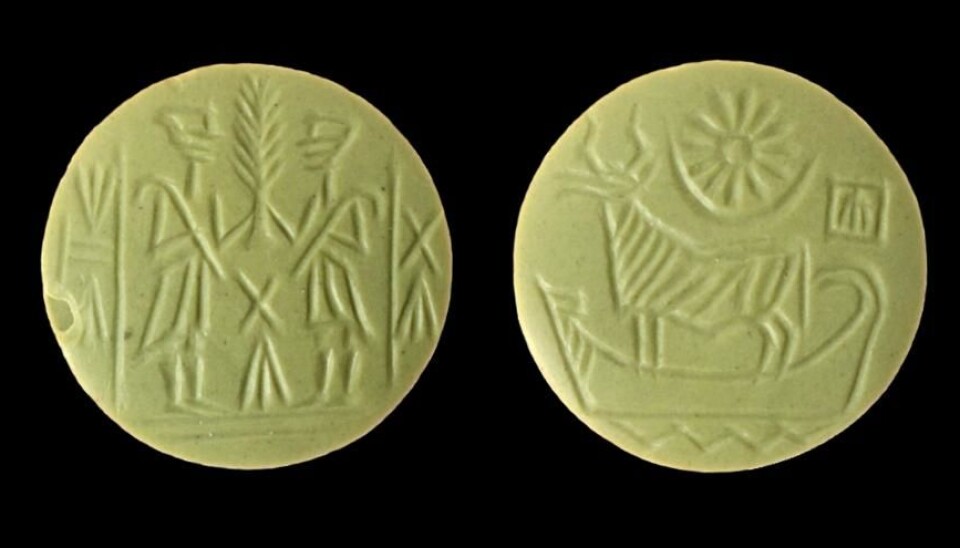

Among the finds, they discovered carnelian and jasper, which were commonly used to produce beads and intricately decorated stamp seals. Although the archaeologists do not know for certain that they were used for this purpose.

Read More: Archaeologists develop new technology to read ancient documents

Evidence of 3,500 year-old global trade

Højlund and colleagues have made an important discovery, says Assistant Professor Kristoffer Damgaard, from the Department of Cross Cultural and Regional Studies at the University of Copenhagen, Denmark.

“It’s an important and historically critical discovery, I’ve no doubt about that. These are the raw materials to make luxury items for a social elite, which makes the discovery something special. It not only demonstrates that the local craft traditions used imported materials, but also that local elites were still able to trade long-distance in expensive commodities such as semiprecious stones,” says Damgaard.

The finds offer a rare glimpse into the infancy of globalisation, he says.

“It’s a fantastic example of how far back globalisation reaches. 3,500 years ago there were already well-documented connections, which were driven by trade. That’s not new knowledge, but it’s rare that we find such concrete archaeological evidence [of it],” says Damgaard.

Read More: Ancient ring brings Vikings and Islamic civilizations closer together

Semiprecious stones were witness to a renaissance time

The semiprecious stones are the first evidence of trade during this period.

“The discovery changes our understanding [of the period],” says Højlund. “During this dark age, Kuwait must have re-established the trade routes, which collapsed around the year 1700 BCE. It bears witness to a renaissance in Bahrain and Failaka around 1600 BC, when it resumed relations eastward with Pakistan and India,” he says.

“It’s a revival of the proud past that we didn’t know anything about before.”

Damgaard agrees.

“The discovery is made more interesting as it comes from a time where trade is history seen as a closed chapter,” says Damgaard.

Read More: The Viking Age should be called the Steel Age

Archaeology should challenge 'truths'

Damgaard is critical of the use of the term “dark ages.” This time was not uneventful, it is just that we know very little about it, he says.

“It would be very strange that they suddenly ceased trans-regional trade in the area near Failaka around 1700 BCE. I’m not surprised that the new discovery confirms that trade continued. But it’s exciting to have concrete evidence, and this shows us that archaeologists can and should challenge “historical truths”,” he says.

According to Damgaard, the new discovery in Failakais a good example of how archaeology should work.

“It’s the archaeologist’s task to ask questions of the historical narrative. Just because historical sources tell us that the trade in Dimun suddenly stopped, it isn’t necessarily the case,” he says.

“Archaeologists are justified in challenging the story with the help of other forms of evidence. This is a great example of that,” says Damgaard.

---------------

Read the Danish version of this story on Videnskab.dk

Translated by: Catherine Jex