A 300-year-old murder could be solved

A skeleton found in a German palace this summer could clear up a missing person case. Royal love letters could have been the motive for an order to kill a count. Could a murder mystery be solved now with DNA evidence?

Workers recently came across a skeleton during the restoration of Leine Palace in the German state of Lower Saxony (Niedersachsen). The bones and remnants of clothes have been examined by doctors but they couldn’t ascertain the cause of death.

However, this is where the young Swedish Count Philip Christoph Königsmarck is thought to have vanished without a trace in 1694.

“If the remains prove to be the young Swedish count who disappeared 322 years ago, he could have been the victim of a royal murder triggered by jealousy,” says historian Håkan Håkansson. He has studied over 300 coded love letters at Lund University in Sweden.

These show that the count and the duchess had a totally improper romantic relationship.

Unhappy marriage to a prince

The count was only 29 when he disappeared. He had a long-going romantic relationship with his childhood friend Sophia Dorothea. She was regrettably already married – and not to a historical nobody.

At the age of 16 she had married off for political reasons to a six-year-older crown prince, Georg Ludwig of Hannover. He later became King George I of the UK and Ireland.

But it was an unhappy marriage, and Georg and his parents were cold and reserved toward the Duchess Sophia Dorothea.

Count Philip disappeared after a nocturnal assignation with the princess.

Love letters

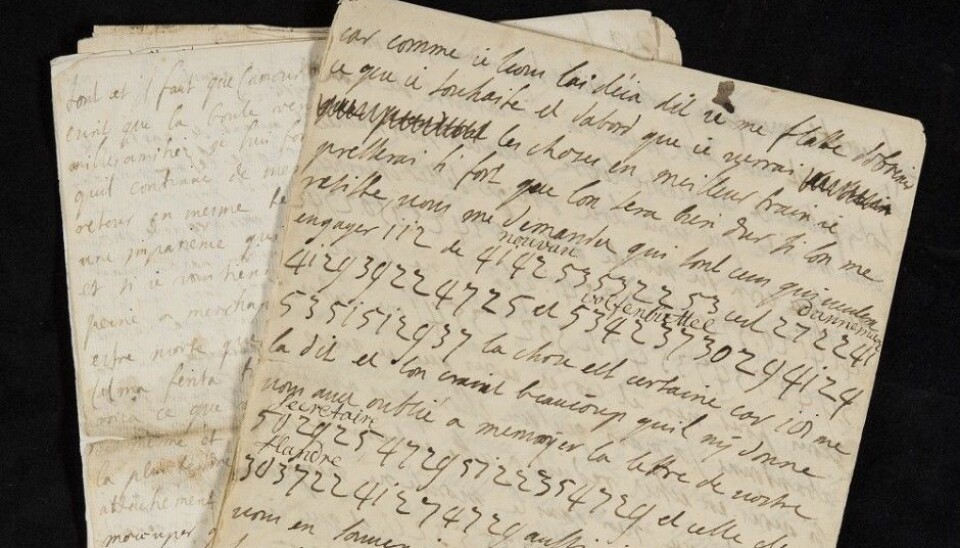

Count Philip and Sophia Dorothea were ardent correspondents. Over 300 letters, sent during a two-year period, still exist. The turtledoves sent an average of three letters to one another per week.

The letters were donated to the university in the early 1800s by Pontus de la Gardie, an eager collector of archive material from Swedish noble families.

These are now kept by the Lund University Library.

“It was not unusual for people to write so many letters in these times. They often wrote many letters a day,” says Håkan Håkansson, an associate professor in the history of ideas at Lund University.

Many of the letters also include numerical codes, cyphers, a feature that was not so common.

“The encrypted language was used to conceal sensitive information. But this one was decoded back in the 1800s,” he explains.

Rather innocent, but scandalous

The numeric code was very simple, with each number representing a letter in the alphabet. When the sweethearts switched from ordinary remarks to sweet nothings they simply wrote in the numeric code.

The encrypted contents were quite innocent from a modern perspective.

Prince Georg was also notoriously unfaithful, bedding down with many women. In the 17th century, as in other times, it was normal for powerful men, particularly kings, to have multiple mistresses.

“But it was much worse, in fact scandalous, for a princess to have extramarital relations,” says Håkansson.

Although the young lovers tried to keep the contents of their letters covert, they would have needed confidants to deliver their letters. This could have been the Achilles heel of their relationship.

Speculations about the children

Sophia Dorothea and Georg Ludwig had two children, a daughter who later became the mother of Frederick the Great of Prussia, and a son who became King George II of the UK. In their day, there were rumours about that the Swedish count was the real father of these children.

“If the children were illegitimate, it would have impacted the claims of the British and the Swedish royal houses,” explains Håkansson.

Researchers, however, have later calculated that the children were born before Sophia could have had sexual relations with the Swedish count.

Historians have also questioned whether the letters were forgeries, made by enemies to undermine the royal houses.

“But we have known for some time now that these letters are authentic,” says Håkansson.

Planning to run off

In the summer of 1694, Philip Königsmarck and Sophia Dorothea planned to run off together. But this did not pan out.

Their love affair was exposed, probably by their friend, the Countess Clara Elisabeth von Platen.

The scandal was out in the open and Count Philip just disappeared.

Sophia Dorothea was sent away and locked in the Ahlden Palace in Lüneburg, not far from Hannover. She spent 30 years there, until her death.

Contemporaries suspected that Georg Ludwig had the count assassinated, but no body was found.

DNA of relatives

Researchers would like to compare the DNA of the bones that have been found this summer with living relatives of Philip. The DNA tests will be done at Germany’s University of Göttingen.

“A relative of the Swedish count consented to help and has provided a DNA sample,” says Håkansson.

This might clear up a murder mystery that has been a cold-case for over three centuries. But Håkansson thinks it unlikely that the skeleton will turn out to be Count Philip.

“It’s evident that this unfortunate individual did not die a natural death. He was found in a palace, rather than buried in a graveyard,” says Håkansson. But he points out that there are all sorts of possibilities for this to be someone other than the Swedish count.

“There are hundreds, perhaps thousands, of persons who could have been in the palace at some time, either servants or guests. So I think this is most probably someone else,” says the Swedish historian.

Click here to watch a video from Lund University about this tragic love story:

--------------------------------------

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no

Translated by: Glenn Ostling