“Viking Tower” excavated in Denmark

Totally unique in construction and unknown to Danish archaeology, extraordinary discovery from the Viking Age uncovered in Jutland.

Wind the clock back 1,300 years to the beginning of the Viking Age in Denmark. We find ourselves in Jutland, Denmark, about 15 kilometres west of Viborg. The river system runs nearby, connecting the area with the hugely important trade and transport route in Limfjorden.

Somewhere on the horizon, a building stretches up into the sky. It is ten metres high, supported by large, heavy posts.

“It could be seen from some distance away. It must’ve been an impressive landmark for the place and for the nobleman who lived there. It’s unique in its construction and would have required a great deal to build. I really wonder where they got the idea from,” says archaeologist Kamilla Fiedler Terkildsen, curator at Viborg Museum, Denmark.

The discovery is described in a new study published in the Danish Journal of Archaeology.

No counterpart in Danish archaeology

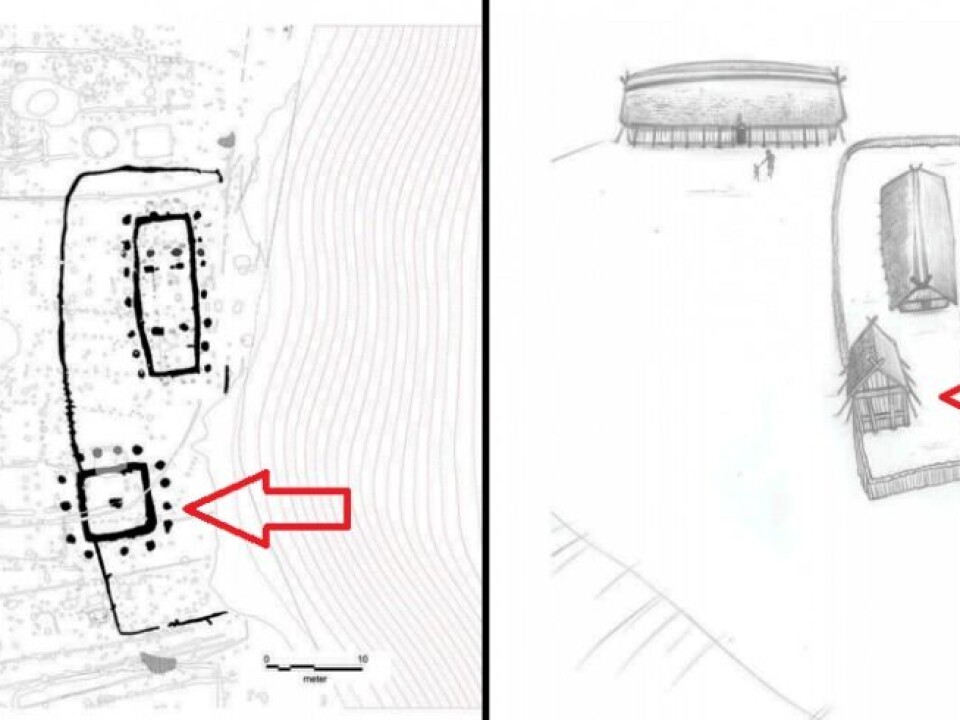

Terkildsen and her colleagues from Viborg Museum uncovered the historic tower during excavations of a settlement from the Viking Age back in 2014.

They could not believe their own eyes.

It appeared that they had uncovered a Viking Age tower—the first of its kind in Denmark.

The tower was first spotted as cropmarks on aerial photos, before the excavation began. But it was a style of construction not previously known in Danish archaeology, so they sought a second opinion from the National Museum of Denmark in Copenhagen.

“They called and asked if I have ever seen something similar. I hadn’t,” says co-author Mads Dengsø Jessen, and archaeologist at the Danish National Museum, who helped Terkildsen excavate the tower.

Read More: New Viking graves discovered in Denmark

The tower stands out from other places

The tower would have formed part of the entrance to a large settlement with several impressive halls, the like of which are found in just a few places in Jutland.

Foreign coins and jewellery show that the site had contacts with Western Europe, and archaeologists have also discovered a fenced house of worship—a type of ceremonial building used for performing rituals.

But the tower is the standout feature, says Terkildsen.

“The site itself is very interesting and one of the few examples of the presence of a chieftain in Jutland, but we emphasise the tower, because there’s nothing like it anywhere else,” she says.

Read More: What colour did the Vikings paint their houses?

An inward-looking tower

The tower dates back to the 700s CE, in the Iron Age. But the entire site was active up until the end of the Viking Age, around 1000 CE.

The materials discovered suggest that it was an expensive and cumbersome build, and puzzlingly, the tower would have had a poor view over the landscape.

But this was probably not what the tower was intended for.

“You’d have to be many meters above the ground in order to see all the way to Viborg, which is what we initially assumed they’d wanted to be able to do. But you can’t do this from ten metres, and that was a bit of an eye opener,” says Jessen.

Read More: Archaeologist discovers a new style of Viking combat

Nobleman watched over his workers

The tower, halls, and ceremonial house are all located on the southern end of the settlement on higher ground.

Archaeologists have not yet been able to excavate the entire northern part of the site containing the so-called pit houses: smaller buildings that would have housed workers and workshops.

But they know that there were pit houses here, based on aerial views, georadar measurements, and test excavations.

Using trigonometry, they can calculate that the tower would have provided a viewpoint over all of the pit houses and the river system in the valley below.

“You couldn’t see very far, but you could monitor the river valley, which you can’t do from the ground. So the question is whether the pit houses were workshops or residential, or both. One could imagine that the owner wanted to keep an eye on the workers on site,” says Jessen.

Read More: Archaeologists discover a Viking toolbox

The Vikings traded slaves

The tower construction was probably built by a chieftain who wanted to watch over his workers, says PhD student Torben Trier Christiansen, who has worked on metal rich sites and detector finds in the Limfjord area.

These workers could have been slaves, he says.

“This was a time where we know slaves became a commodity. Written sources from southern Europe indicate that the Vikings abducted and captured people during their many raids,” says Christiansen.

“The Vikings eagerly engaged in the slave trade, and the question is whether or not slaves were responsible for basic production [in Viking societies],” he says.

“If so, there could well have been an incentive and basis for extreme surveillance and control,” says Christiansen.

Read More: New study reignites debate over Viking settlements in England

“An important, exciting construction”

“It’s an important, exciting construction, that represents a massive investment of work and materials. For me it’s an important finding, because here there’s physical evidence of a problem, which we can assume is bigger than just this one place,” says Christiansen.

Jessen warns against viewing sites like this as isolated from the wider world. There was extensive trade and awareness of the world.

“One always underestimates how much they knew about the world around them at the time. We think that they didn’t know that much about each other, but of course they did,” he says.

---------------

Read the full story in Danish on Videnskab.dk

Translated by: Catherine Jex