‘Reptilian’ brain is a penny-pincher

A primitive sector of the brain, the amygdala, affects financial decisions. But how do we explain a big difference in men’s and women’s altruistic actions?

Researchers from the Karolinska Institute have found significant differences in brain signals between real and hypothetical choices.

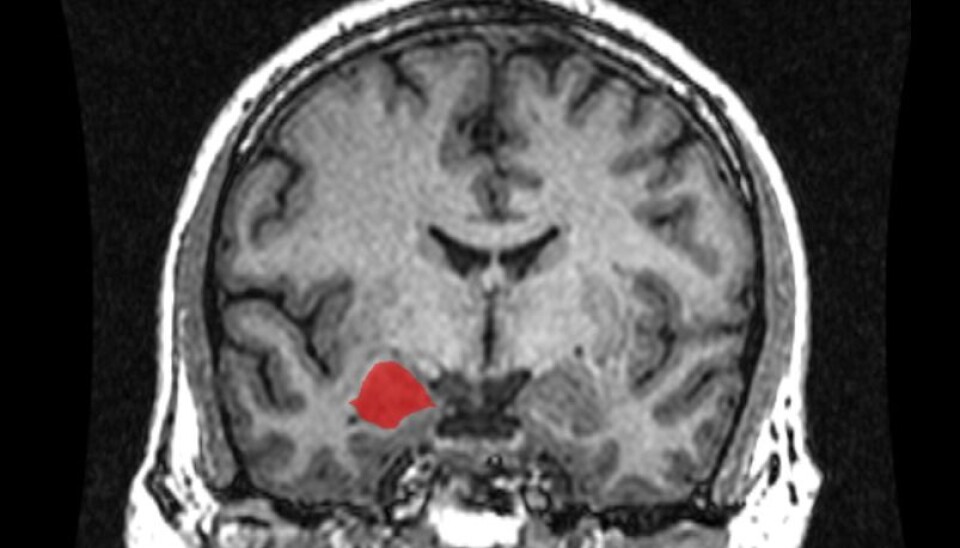

“We discovered that activity increased in the amygdala, also called the reptile brain, when test people made real decisions to donate money — more so than when their decisions were simply hypothetical,” said Katarina Gospic, a researcher at the Department of Clinical Neuroscience, Karolinska Institute (KI).The researchers believe their study is the first ever to show this kind of difference.

By scanning brains of test subjects with functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) the scientists at KI, in cooperation with Sweden’s Royal Institute of Technology, determined that our primitive reptile brains are at play when we make decisions about money.

The study divided 38 people into two groups. Their brain activities were monitored while they decided how much money they would donate to various charities.

“The one group was asked to make hypothetical, but realistic, donations. These wouldn’t really cost them anything. Members of the second group were told that their donations would actually go to the organisations they selected. The activities monitored in their brains differed significantly from one group to the other,” says Gospic.

Emotions and rewards

The amygdala is a primitive structure of the brain that is guided by emotions and that reacts very rapidly.

“We instinctively wish to avoid unpleasantness or losses and often take the path of least resistance. But in our study we found the test subjects had to be able to regulate impulses from the amygdala in order to donate money to charitable organisations,” Gospic said.

“When the study participants made a real decision about a donation, we saw a rise in brain activity in the rACC (rostrala anterior cigulate cortex). This is the structure in the brain that regulates emotions and restrains impulses from the amygdala. At the same time, we also saw an activation of the striatum, the brain’s reward structure,” explains Gospic.

She believes that this is a matter of weighing losses against rewards in these kinds of financial decisions.

“It’s the amygdala that makes you instinctively jump over a branch on the ground that might be a snake. This happens really fast because if it really were a snake, your reaction time might be too slow if you had to process the information in the rACC in the frontal lobe.

“The instincts from the amygdala can save us from treacherous situations, including stepping on snakes, but the amygdala’s instinctive reactions aren’t always correct. Sometimes other elements have to be included to override primitive signals and give us advice. Along these lines, a disadvantage, a fear of a potential economic loss, can be weighed against a future gain,” explains Gospic.

Gender differences

Gospic says that we are generally more altruistic when the choices we make are hypothetical rather than real economic decisions.

But the researchers were surprised to discover gender differences in this respect.

“We saw that women followed the expected norm and donated more money to charity in the hypothetical donation group than women in the group who were really making monetary donations. However, men in the real donation group gave away much more money than men in the hypothetical donation group.”

“The results showed that men — in contrast to women — were much more generous in real economic situations. This was a result we hadn’t anticipated,” says Gospic.

She is at a loss to explain this gender difference.

“I can’t say why we got this result. All I can do now is speculate and if there is one thing scientists dislike it’s speculation. I can say, however, that we will be giving this a closer look in upcoming studies,” says Gospic.

---------------------------

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no

Translated by: Glenn Ostling